Welcome to the Century of the Vampire, an ongoing weekly feature where Goonhammer managing editor Jonathan Bernhardt watches some piece of vampire media, probably a movie but maybe eventually television will get a spot in here too, and talks about it at some length in the context of both its own value as a piece of art and as a representation of the weird undead guys that dominate western pop culture who aren’t (usually) zombies.

Today, he looks at the 1922 F.W. Murnau film, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. This article will contain spoilers.

And now, all the way back to the beginning. The original vampire movie. Fitting that it began with hurt feelings and lawsuits about creative theft, given the entire genre it spawned has been filled with people suing each other over stolen ideas and trademark infringements. Lucky that there are copies remaining at all!

You can watch the entire thing for free online if you want, since the copyright has expired on this film; here’s the YouTube link to version that’s most preferred on archive.org:

It’s neither novel nor surprising to note that this is not a particularly scary film to the modern eye. It was not particularly frightening to contemporary audiences, either; what few saw it, at least. Critics at the time more accurately pegged it as moody; Murnau worked in the German expressionist tradition that favored emotion over realism, and what that meant in practice was a lot more high-theater acting with exaggerated movements and facial expressions along with lots of very expensive stunt, staging, and effects work that was at the time very new and compelling but which seems very rudimentary when watching it today.

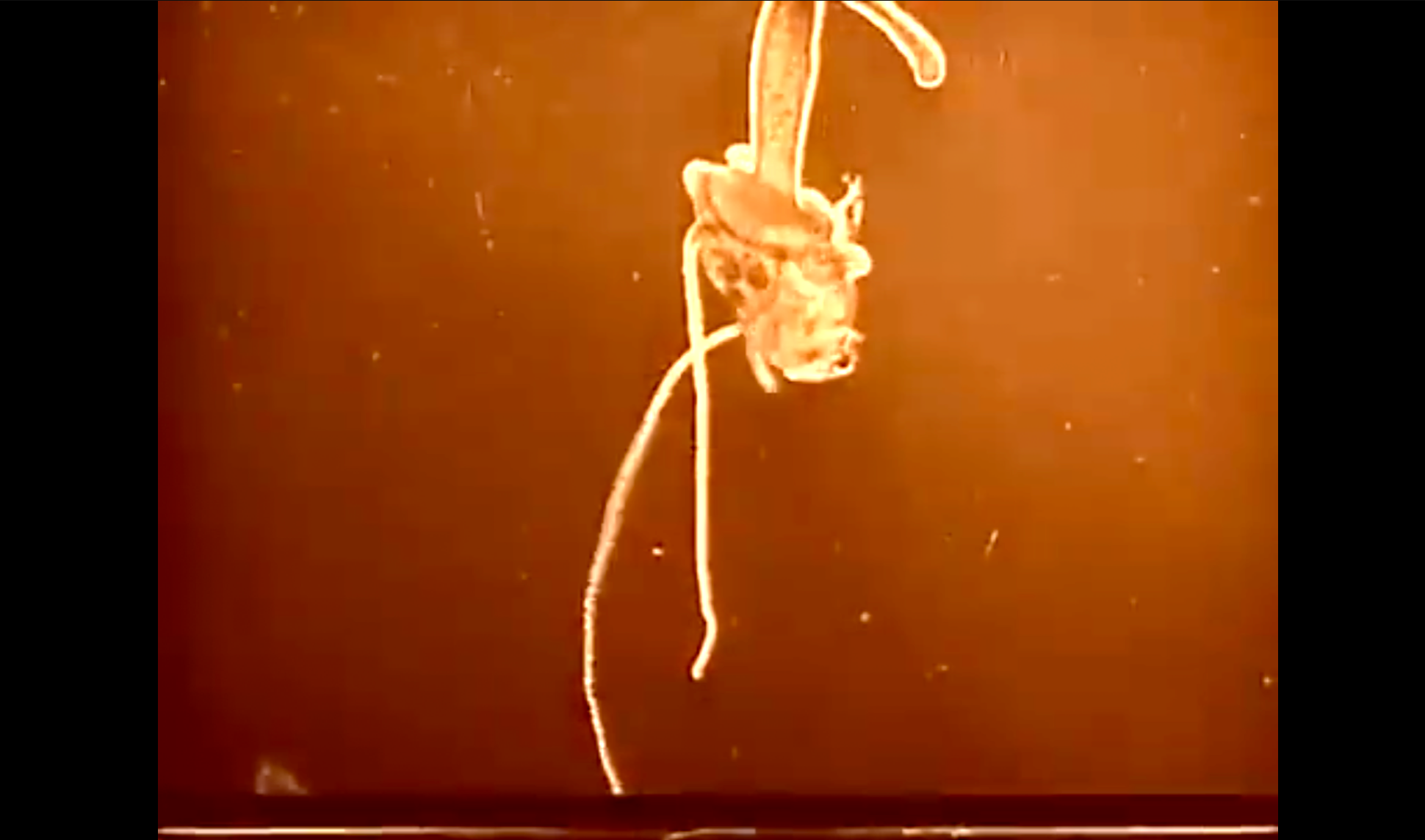

This column is not particularly interested in all of that production history! We’ll have more to discuss about it when we get around to Shadow of the Vampire in a couple weeks. There is, however, one observation to be made that doesn’t really fit there or anywhere else in this piece: Murnau, casting about for any means of showing the act of vampirism with a very rudimentary set of tools in his effect toolbox, happened upon an excellent way to use realism and naturalism in service of his expressionist goals: Nature photography. Nosferatu deploys the van Helsing-like Paracelsian Professor Bulwer almost exclusively as an excuse to get the good doctor showing students the up-close workings of a Venus flytrap, a polyp with tentacles, and a spider eating its prey, all in service of conveying something about the nature of the title monster. These are a bit tenuous as thematic devices — especially the polyp — but they were impressive technical feats for 1922, and earn their place in the film essentially through the Rule of Cool.

But we’re concerned mainly with the most enduring part of Murnau’s film, the one that had the most direct downstream effect on popular culture, vampire and otherwise, and whose own place of prominence historically is part of what neuters any real horror in this film: That weird little guy, the big bad Nosferatu himself, Count Orlok.

In the text of the film, Orlok is not supposed to be endearing. He is not supposed to be funny. He does move around with extreme exaggeration, because that’s the style of filmmaking being employed; Hutter, for his part, bounces around like a madman when he’s happy, swoons and sighs when he’s sad, puts on comically horrified faces when he’s scared — in fact, one of the genuinely creepiest parts of the film to my eye had nothing to do with the vampire himself. It was this shot of Hutter, having just picked some flowers for Ellen, sliding through the front door with a smile as he prepared to sneak up and surprise her with them. If a man with that smile slides through an off-centered doorway into frame in a modern movie, you as a viewer are supposed to be startled and either put off or outright threatened by him — especially with the degree of unreality in that lighting! But Hutter’s just being a nineteenth century wifeguy here.

Orlok, on the other hand, moves about the screen very very slowly, when he’s not teleporting (except for one very notable scene where he is not slow at all, which we’ll get to in a minute). We get to see a lot of him, because the costume design and makeup work is there to be seen — the genre conventions of horror haven’t developed yet, and in 1922, “a really strikingly visually weird creep” is the sort of thing you foreground in your motion picture. He’s tall and, while gaunt in proportion to the rest of his body, still shot in a way that makes him appear really big; actor Max Schreck was said to be 6’3” and clearly has some height over his co-stars, but Murnau manages to make him seem a few inches taller than that during some of Orlok’s most ominous scenes. So what’s the problem here, to the extent there actually is one?

You already know what the problem is: He kinda looks like a big baby from the neck up. A big goofy baby with huge, expressive eyes. This is why Eggers threw a mustache, a long mane of hair, and usually a hat on his version of Orlok. The giant needle teeth (Orlok is a front-teeth puncture guy instead of biting with the canines like later vampires in the western canon) try their best to make him look gnarly; half the time they give him a beaver-like quality. In stark counterpoint to Hutter above, Orlok slowly emerging from the hold of the plague ship into Wisborg doesn’t give off apprehension or ominous terror so much as, “Hey. Hey there, little guy. Nice to see ya.”

This actually brings us to the interesting part of the film; the first and second acts of Hutter traveling out to the Carpathian Mountains and getting stuck there in Orlok’s castle are the most famous parts of the film not just for the production issues they’d have that would eventually inspire Shadow of the Vampire, but because they’re engagingly paced and shot. When Orlok arrives back in Wisborg, the wheels of Nosferatu 1922 start to come off a little in interesting ways.

The first way — less interesting, but it’ll lead into the second — is that the Renfield stand-in real estate agent Knock becomes, in this original version of the tale for the screen, a strange parallel antagonist alongside Nosferatu rather than a cringing helper or second to him. As Orlok departs the plague ship Knock breaks out of the asylum to which he’s been consigned, but not to aide his master directly; instead, he roams about the city, climbing atop things he shouldn’t and being a general nuisance until a mob forms, blaming him for the plague. They are indirectly correct! For the remainder of the act this attempt at a lynch mob chases Knock about Wisborg and out into the fields, at which point he fools them with the old ‘put my coat on a scarecrow’ trick and slips away, only to be…recaptured offscreen and returned to the asylum. This is flabby storytelling that seems to be mostly there to get some emotional action on screen with the mob and let the actor playing Knock, a 28-year-old Alexander Granach in elderly makeup and a bald cap, show off his core strength by climbing over stuff; Eggers was correct to rewrite the character back into the expected cringing servitor that developed for the Renfield character over the intervening century.

But more importantly, this means there’s no one to move Orlok’s coffin but Orlok. Our chilling master vampire villain emerges from the plague ship with a goofball grin on his face, picks up his coffin under his arm like an awkward bag, and clambors off through the empty streets of Wisborg to his new residence, his journey intercut with Hutter’s return home to Ellen and the spread of the rats themselves. If one’s being indulgent of the original intention of the work, it shows the unnatural strength that the vampire has to have in order to move a coffin full of soil with such ease. If one has lived in New York City for any length of time, one recognizes an echo stretching back through the years of that semi-common sight: The guy with a package he thought he could just pick up and take home on the subway instead of paying to have it delivered, and who is stubborn enough to be right about it no matter how silly or inconvenient it looks.

Murnau’s Orlok is utterly iconic, and each subsequent iteration of him tries to do something different to actually make him scary, instead of visually arresting and creepy, but bordering on funny. Eggers changed the design entirely, making him conform more to warlike Hun imagery with his pelts, long shaggy hair and mustache; Herzog, as we’ll see next week, hired an actual monster of a man to play the vampire in Klaus Kinski — the absolute values of the character design haven’t changed much, but he is a completely different creature even in stills. And Shadow of the Vampire leans into the theatricality of the original Orlok design with Dafoe’s “always on” Max Schreck. But the character that reminds me most of this Orlok in pop culture? It’s probably that Gru guy from the Minions movies. That character intentionally uses the severe over-exaggeration of seriousness for comedic purposes (whether he’s actually funny is, well, to taste) whereas in Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror it’s an unintentional artifact of the distance between cinema now and cinema then, but there are a lot of emotional and kinetic similarities between the cartoonish CGI animation of a character like Gru and the stop-motion and frame-drop speed-up tricks used to show Orlok in action. Even if the simplest one is just Max Schreck motoring down an empty street carrying a “full” coffin of soil.

Next week, it’s Werner Herzog’s 1979 Nosferatu the Vampyre, which I have neither seen nor particularly looked into before. I know Herzog mostly from his documentaries and latter-day presence as a source of memes on social media; my only familiarity with him in dramatic work is as an actor in the Star Wars TV show with the Yoda baby and as the old disfigured Nazi villain in the 2012 Tom Cruise Jack Reacher movie. In both, he conformed precisely to the social media memes; I’m interested to see how he’ll be behind the camera (and in his minor on-screen role, Hand and Feet in Box with Rats).

In two weeks, it’s Shadow of the Vampire; in three weeks, it’s…something that hasn’t been chosen yet! The Patreon poll for Goonhammer subscribers to determine what vampire film I’m going to watch and have vampire thoughts about next will go up either by the time the next one of these columns is published (in which case I’ll have a list of candidates) or soon after. I’m going to insist that Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) is on there. We’ll see what else winds up as an option.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.