Welcome to the Century of the Vampire, an ongoing weekly feature where Goonhammer managing editor Jonathan Bernhardt watches some piece of vampire media, probably a movie but maybe eventually television will get a spot in here too, and talks about it at some length in the context of both its own value as a piece of art and as a representation of the weird undead guys that dominate western pop culture who aren’t (usually) zombies.

Last week, Bernhardt reviewed the 1992 Francis Ford Coppola film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Today, he looks at the 1931 Tod Browning film, Dracula. This article will contain spoilers.

The film was a critical success and box office hit on its release; it obviously made Bela Lugosi’s fame, if not his fortune — Lugosi, a socialist in his youth and an addict in his later years, never reaped the material rewards that the studios did for using his name, and he never got out from under the shadow of Count Dracula when it came to being cast in new projects and different roles. As the official, licensed adaptation of the Stoker novel for the big screen it was of course far less faithful to that material than Murnau had been a decade earlier. It is an interesting relic of the transition from silent movies to the “talkies;” originally the part of Count Dracula had been tabbed for Lon Chaney’s first speaking role before the actor passed tragically young in 1930. This is all a roundabout way of saying that in 2025, Tod Browning’s Dracula is not an especially compelling watch.

First, the good: Lugosi. Lugosi’s performance is the only reason to actually look this film up unless you’re doing specific research on period techniques for effects (the bats are extremely funny) or writing a paper on the similarities of early Hollywood screenwriting to live theater. Lugosi is the only actor treating this enterprise with anything near the seriousness required to get material like this over with an audience; his foil and the real protagonist of the film, Dr. Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan), is the closest second, but his is a workmanlike effort from an actor who had great disdain for the project. The third most prominent role in the film is somehow Dwight Frye’s Renfield, who is irritatingly overcooked and gratuitously overexposed, escaping his comic relief orderly to barge into scene after scene to explain the plot and Dracula’s motivations to the audience with as much exaggerated pantomime as any silent film character. John Harker has all of his duties from the novel reassigned either to Renfield or Van Helsing, leaving a bland, airheaded fiancé who would suffocate if the doctor wasn’t around to remind him to breathe. The women, Mina and Lucy, are one-dimensional victims for Dracula and Van Helsing to move about the board in their duel of wits — we barely get to meet Lucy before she’s dead on a slab in Van Helsing’s operating theater, and the script’s treatment of Mina is both so dull and so high-handed as to make us wish it had such quick mercy for her as well.

At the intersection of all this film’s problems is the fact that it’s an adaptation of an American stage play, rather than a direct adaptation of the novel itself. Early American film shared many of the same logistical problems that a stage play would have in bringing the story of Count Dracula to life: You can’t stake and decapitate Dracula live on stage (or at least not before closing night); you can’t show Dracula turning into a wolf or a bat or rats; you can’t show Dracula drinking anyone’s blood — especially if you’ve either got no imagination or don’t want to upset an increasingly irate right-wing coalition of religious and political leaders by using it. (Three years later, they’d get the draconian censorship of the Hays Code anyway.) So everything interesting happens off screen in this film, usually with Renfield or Van Helsing then describing it for the audience.

Other than the vampire theatrically looming over people to imply that he is about to feed upon them as the shot fades to black, the main “action” the movie is willing or able to show is Dracula’s power of mental suggestion and hypnosis, of which he constantly avails himself. This is actually a good thing, because it means we get the only memorable and striking images of the film: Close-ups on Lugosi’s face with highlights across his eyes as he deploys a menacing charisma. Outside of some excellent set and backdrop work by the studio prop and design crews, these were the only parts I found myself marking down during my watch to later grab images from. And there are so many! At least six separate instances in 74 minutes of runtime, and I’m fairly certain I didn’t grab one or two during the first ten minutes when Renfield journeys to Transylvania to sell Carfax Abbey to Dracula (replacing Harker).

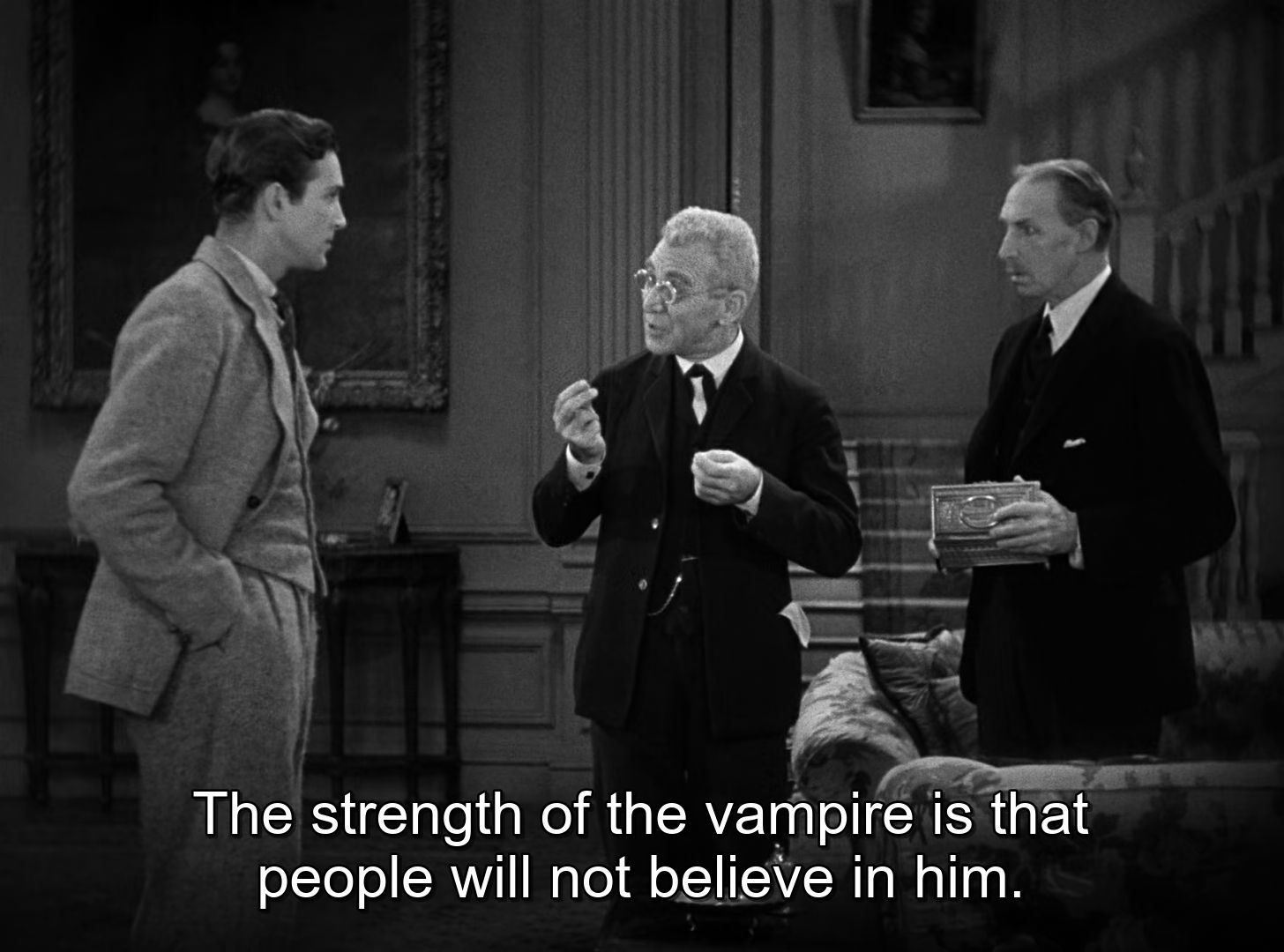

Whereas other treatments of the work highlight the vampire’s connection to the object of his obsession, the Mina/Ellen character, here the only character able to resist Dracula’s dreadful powers of the mind is Van Helsing. This film is the genesis of the pop culture positioning of these two as rivals on any sort of equal footing; by giving Renfield all of Harker’s Transylvania story beats, making Dr. Seward into Mina’s doting, ineffectual father and getting rid of Quincey Morris and Arthur Holmwood altogether, only Van Helsing is left to have any momentum or agency in opposing the vampire. And indeed when they first meet in the drawing room (another sign this was originally stage play is how much of the important action takes place in Dr. Seward’s drawing room and Mina’s bedroom) the Count notes that Van Helsing is such a famous, bold, and respected expert in his field that word of his exploits has spread even to Transylvania. Within three minutes, Van Helsing has determined with the help of the mirror in a cigar box lid that Dracula is a vampire, and the question becomes whether the heroic doctor can convince Seward and his idiot family of the dangers of the Count and increasingly of Mina herself as she falls under the vampire’s spell, before irreversible damage is done.

The answer is… probably? Unlike in every other adaptation of the material I’ve previously watched, Van Helsing’s plan of simply following Dracula as he walks back to his coffin, waiting for him to go to sleep, then staking and decapitating him just flat-out works. Dracula blames Renfield for this and clearly we’re meant to believe it was Renfield they followed instead, but the vampire literally just runs off carrying Mina and they follow him back to Carfax Abbey, the place he repeatedly told them all that he lived. They could have done this any morning after breakfast since the revelation in the drawing room! The end is so abbreviated and perfunctory that you can read some “Is Mina still a vampire under his thrall?” into the final couple of shots if you so choose, but they seem abbreviated and perfunctory in service of getting out of there and hitting the end card, not in service of ambiguity.

Lugosi really is very good. It’s not his fault they turned a fine steak into a cheap American hamburger around him. The Murnau film from almost a decade prior has its eccentricities but at least when it wasted time with the Renfield character, it had a guy in a bald cap and age makeup running across rooftops, climbing up things and jumping down them. The battle for Renfield’s immortal soul as his compelled service to Dracula wars with his love of Mina — he has some past history with and affection for her, possibly as a failed suitor, that the script has very little interest in addressing in any depth — is just profoundly uninteresting stuff, though after Dracula kills him at the film’s climax he does roll down the stairs and into some garbage in a pretty amusing way. Whatever’s going on with the slovenly, clownish orderly that keeps losing track of Renfield and letting him up into the drawing room of Seward’s combination manor house and asylum feels like some kind of boutique old intramural white-on-white racism that we don’t have anymore in 2025. This makes him the third most interesting character in the movie after Van Helsing and Dracula himself. Except for the big man’s fantastic and expressive face, there’s really nothing to see here.

We may look at Lugosi’s later vampire-related work at some point, but nothing compelling immediately stands out (no, we’re not touching the Ed Wood stuff, at least not right now). Instead, we move on to the most notable mid-century Dracula film, starring Christopher Lee as Dracula and Peter Cushing as Van Helsing. Then Dracula 2000, and then…another set of four films that will be voted on by our patrons over at Patreon. Can’t wait to see what they and Rob come up with for me next.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com. Want articles like this linked in your inbox every Monday morning? Sign up for our newsletter. And don’t forget that you can support us on Patreon for backer rewards like early video content, Administratum access, an ad-free experience on our website and more.