Abstract games are regarded as either sacred tomes or four-letter words depending on one’s tastes. Or you can go full galaxy brain and say “in a way, if you think about it, isn’t every board game abstract?” But that’s a pedantic “well, actually” for another time on another platform (such as Hot Take Board Game Twitter™).

In games “dripping” with theme (or “swimming” or “dog paddling” or “drowning” in it… why is theme always expressed as liquid and not solid or gaseous forms?) you are asked to imagine that you are doing the thing on the box cover, playacting at the table. So I’m not literally an innkeeper in medieval Germany, or managing a luxury hotel in Vienna, or wrangling living dinosaurs in a bad-idea amusement park. But I am rolling and mitigating dice rolls and placing workers and taking actions in order to metaphorically do these things, and try to do them well. Theme is a representation of mechanics and rules that, when at its strongest, conjures the “idea” of the experience you are reenacting. Games with theme ask you to suspend your disbelief to further enjoy the experience.

Abstract games can’t be bothered. No suspension of disbelief necessary. No costumes or set design or backdrops or origin stories required. Abstract games explicitly and purposefully don’t “feel” like the thing that is showcased on the tin. Bits on a board represent math and Euclidean geometry. Abstracts get right to it: things are what they seem. Because of this most abstracts leave me cold.

So by all metrics and definitions I shouldn’t like Sid Sackson’s classic game Can’t Stop as much as I do. And I love Can’t Stop. I can’t stop with Can’t Stop and I can’t be the only fan; the game has been in print in various forms online and analog for more than forty years. It has never received an update, reboot, refresh, reupholstered “theme” or even a renaming. Since 1980 we have always had Can’t Stop in its current structural, abstract form. What is Can’t Stop’s secret?

Listen closely and you can hear a cacophony of chippy commenters dismissing Can’t Stop for a symphony of reasons over the years:

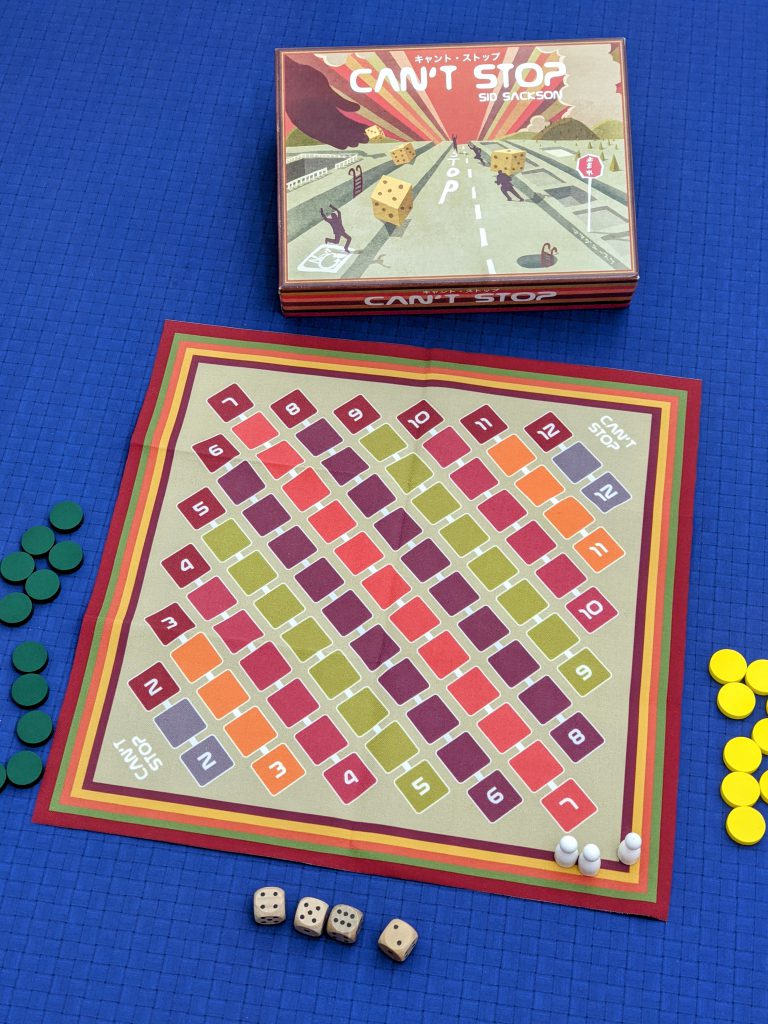

• There’s (not really) a board. It’s not even a scoreboard since points aren’t awarded during the game. The board isn’t a game state. There’s no area to control, no workers to place, no actions to take. The board is a progress report the way a bookmark or dogeared page keeps your place in a book you’re reading.

• There’s very little “game” to it. The goal is to be the first to close out three of 11 laddered tracks (numbered 2-12). Tracks are as short as two rungs (2, 12) or as long as 10 (the 7 track). Track lengths correspond to their 2d6 dice probabilities. So closing out 7 takes more steps because rolling 7’s is statistically more frequent.

You roll four dice on your turn then split them into two dice pairs. The sums of each pair represent which ladder-like tracks you climb on the board. So a dice roll of 2-3-5-6 advances any two of the columns 5, 7, 8, 9, or 11 depending on how you split and choose. This includes the possibility of advancing twice on the same track (in this example 2+6 and 3+5 advances you two spaces on the “8” track).

Your first roll each turn commits you to two tracks automatically, and you are allowed to progress along three different tracks per turn. Therefore, your next roll will progress you along your previous tracks or potentially give you the choice to advance along a third. Once “locked” into three dice outcomes, if you choose to roll again at least one dice pairing from your roll must make a combo that lets you advance along an already-committed-to track. If you roll and don’t make a combo that matches once of your committed tracks, you bust and lose all progress that round. If you choose to stop you keep any progress you made that turn.

• There’s only one meaningful decision to make all game long: to roll or to stop rolling. Over and over and over. If you roll you combine dice into pairs, move up the corresponding open tracks, then decide if you want to roll again or stop. If you stop you keep any upward progress you made on the tracks in the round. If you roll again, you must be able to make a move on one of your tracks. If you can’t use at least 2 dice, then you bust and lose all accrued progress you made that round.

• There’s no economy. There are no resources, there is no currency, no coin of the realm. Not even abstract economies of actions or hand management or workers. Or victory points – of which there is only one awarded each game to the winner. Like chess, every game scores 1-0. Unlike chess, there are no draws or stalemates.

• There’s no conflict and barely any player interaction. Your rolls do not affect other players. Your position on the track can be shared by others. The only interaction is if you close a numbered column first. Then it is closed for everyone for the rest of the game, and future rolls on that number are busts. This can be devilish if you get 7 the hard way; for the rest of the game the most likely number to roll on 2d6 is no longer an option for anyone.

• There’s zero player tactics and very little controllable strategy. You roll or stop rolling. Maybe you close off a track but doing that affects everyone so isn’t an advantage to you. There is some strategy if you care about probability, but understanding that the chances of rolling a 7 are better than the chances of rolling a 12, only takes you so far. You’re still at the whims of “to roll or not to roll” the dice.

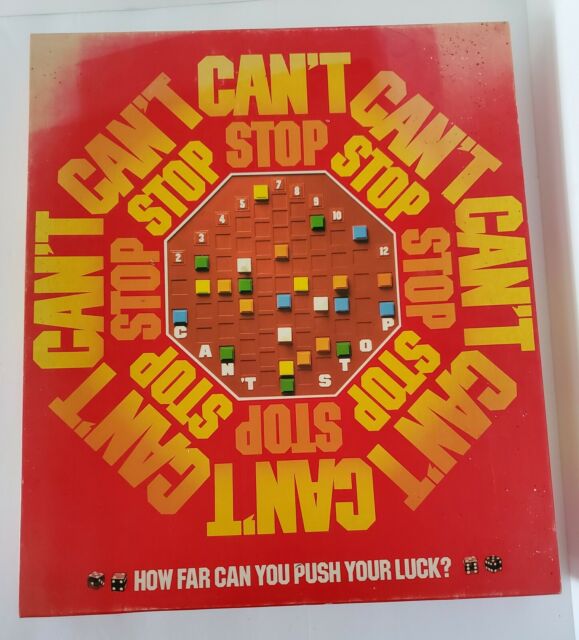

• Can’t Stop is so simple and the components are so ubiquitous that you don’t even need to buy it in order to play it. Two dice, a piece of paper, a pencil. The iconic and garish board and bits are non-essential (not to mention very on the nose: “you see, it’s called CAN’T STOP so the board is a STOP SIGN. Get it?”).

Can’t Stop is an abstract unicorn: it’s math but with zero perfect information. It’s built around a core mathematical concept without enhancing that concept or forcing it to serve added purpose in the game. Here are your chances: roll or don’t roll. You can calculate percentages to the farthest decimal point but still lose to someone who Han Yolos it with a cavalier shrug, says “never tell me the odds,” and defies logic by rolling the dice again and again anyway, climbing to impossible heights on a track. Both styles of play are rewarded by the ever-present fog of luck.

How does this particular abstract game about a mathematical concept, distilled down to its purest essence, transcend abstraction, or ascends from its abstract form to… something else? As if sublimating from solid to gas?

That “something else” is Can’t Stop’s secret sauce: how the game makes you feel while playing it. It’s a bespoke bottle of pressed luck—potent and intoxicating. The dopamine and endorphin rush when you uncork it is immediate and addictive. Even when it’s not your turn, watching someone climb the ladders and choose to roll, and roll, and (hope against hope, improbably, impossibly!) roll yet again is like watching an Olympic event live. Will they stumble? Will they fall from such dizzying heights?

Can’t Stop is also a game that doesn’t hurt that much if you bust or when you lose. It’s all the itchy parts of gambling without the actual debt and painful regret. Games are so fast and there’s so much cubic feet of luck that’s pressed that when you get snakebit by dice rolls, there’s nothing to do but shrug or laugh it off. There’s still the possibility each turn that you can go on a thrilling, epic speed run of luck and climb a ladder to pull out a stunning finish, and you’ll be surprised how much you cheer for others to do the same while you’re playing. Never has four dice had such epic party game appeal.

Can’t Stop feels as old and classic as Go or as Cribbage. Sid Sackson was the just first to package game theory and probability as a playable game, forty years ago. The pressing of luck, the random encounter of each dice roll, the tantalizing decision to roll or not roll is Can’t Stop’s unlimited, renewable energy source. The core component of the game is not the (usually ugly) material pieces in the (usually styleless) box, but the frisson of luck-pressing, of being on rails and not being able to stop rolling, or to stop playing.

Despite it having the strategy of Probability 101, Can’t Stop suspends your disbelief that you are merely rolling dice and throwing darts at an odds spreadsheet. Can’t Stop is given life by the feeling it engenders. Sid Sackson is responsible for creating the most thematic abstract game I’ve ever played because it’s that rare abstract game that somehow is dripping with soul.