Lancer is, according to the back of the rulebook, anyway, “a mud-and-lasers tabletop roleplaying game of modular mechs and the pilots that crew them.” Set thousands of years in humanity’s future, the people of Earth have come together to found Union, a new galactic power founded to build a utopia for all of humanity.

I’ve had a blast with Lancer, having participated in a handful of campaigns since the game’s release, both as a player and GM. The mech combat is at the forefront here, with a crunchy set of rules that lets you build the mech of your dreams, then have it take the field against enemies that have abilities just as weird and wonderful as your own. Add in an advancement system that prioritizes adding new and interesting options to your ever-expanding list of weapons and wargear rather than just having Number Go Up, and you have a fairly tightly-balanced game that rewards creativity both in building your mech and in using the tools you bring into a mission.

That’s not to say the narrative suffers, though: the setting for Lancer is incredibly rich and detailed. Whether you’re looking in the roughly 80 pages of narrative material in the back of the core rules, the multiple supplements available on Massif’s itch.io store, or the short lore entries and vignettes scattered throughout the rules entries to help ground them in the setting, Lancer describes a potential future that is at once completely alien and utterly human. Massive corpro-states war over resources on the fringes of explored space while the residents of those planets rise up in revolt to protect what little they have to call their own. Union advances its utopian project despite resistance from the Karrakin Trade Baronies, who view themselves as the true inheritors of humanity’s legacy—and they might be right, but not for the reasons they think. And the appearance of the enigmatic MONIST-1, an utterly alien “paracausal” intelligence with fantastical powers that defy explanation, resulted in the theft of the Martian moon Deimos to places unknown and the appearance of “non-human persons”—NHPs—who fill a role similar to what another setting might call an AI, if your AI companion could alter the fundamental rules of reality by thinking really weird, that is.

But rather than reviewing the book and going through everything from a player’s perspective, today we’ve gone straight to the source: Miguel Lopez and Kai Tave from Massif Press were gracious enough to sit down with me for a few hours to talk about Lancer, what inspired it, what humanity looks like in 5016u, and how it completely ruined their YouTube recommendations feeds.

Condit: I guess before we kind of dive into Lancer itself, Miguel can you introduce yourself to the readers, let us know where you’ve been, where you are, and where you’re headed?

Miguel Lopez: Yeah, sure. Where I’m headed. Hopefully, somewhere good. Well, so hi, readers. My name is Miguel. I guess at the time of making Lancer, we didn’t really have titles, but I guess I would retroactively apply the title of narrative designer or lead narrative designer. It’s at least what I’ve put on my resume. But I, along with Tom, co-wrote Lancer and co-founded Massif Press, and have for the past few years… Prior to that, I worked independently, mostly table service, while trying to get through grad school and working on my own fiction. Got Lancer going with Tom, and then after a couple years of co-running Massif Press and leading Lancer, got hired on by Wizards of the Coast on Magic: The Gathering.

So now I am… So my official title is a world-building game designer. Basically, a narrative designer over there as well. So that’s where I’m at currently. I don’t actively work on Lancer anymore. I’m still a partner over at Massif Press, and I have some, essentially, editorial, more or less, oversight over our current and forthcoming releases. But for the time being, I’m over at Wizards working on Magic, a Magic story basically, and sort of mainline card sets.

Condit: And Kai, same question, how did you get involved with Lancer? What brought you here? What are you doing with Lancer now? What’s coming in the future?

Kai Tave: So I did not co-found Massif Press. I was not really there at the beginning, except as just a fan. I actually found out about Lancer because I was reading a thread on the Something Awful Forums for Tom’s webcomic Kill Six Billion Demons. And I knew he had done some RPG design stuff before he did a Powered by the Apocalypse sort of hack for Kill Six Billion. And somebody in there posted a link and said, Hey, it looks like he’s doing a mech RPG that’s got a lot of fourth edition Dungeons & Dragons in it. So mechs and fourth edition D&D are two things that I really like. So I said, oh, okay, this seems cool.

So I got into contact with Tom mainly just giving him feedback on things that I read in the document. It’s like, this seems cool, but it’s kind of unclear. Maybe the wording could be better here. Basically, I was just giving him playtest feedback. And at some point post-launch, after the game was out, they were working on the big narrative campaign module, No Room for a Wallflower, and Tom asked me if I wanted to come and do some sort of developmental editing on the project, which was… My job was basically to take a lot of the story beats that had been compiled so far and arrange them in a fashion that could actually be played through easily. Because it was sort of scattered, it was kind of all over the place. They also needed someone to work on the actual combat encounters, which had not been drawn up, how many NPCs, which NPCs we’d use.

So that was the first real project that I did for Massif Press. After that, the tabletop app Role, they wanted to do some stuff involving Lancer. What they were looking for is they were looking for games that they could use for their tabletop services, kind of a demonstration of what they were up to.

Condit: Yeah, if I remember, it was sort of some stretch goals for their Kickstarter.

Kai: And the thing is, at the time Role did not know that if they were going to have any sort of map functionality on their service, they were going to be having voice and they were going to be having video and they were going to be having some other features, but they didn’t know if they were going to have an actual virtual tabletop.

So I believe what happened is they approached Massif Press and said, could you do a version of Lancer for us that doesn’t use a battle map? And that would’ve been very difficult because Lancer is a tactics combat game first and foremost. It would’ve had to have been a complete overhaul of everything. And I believe it was Miguel who said, well, we can’t do that, but what if we did a different game that doesn’t have to have the grid map? Because he had been sketching up ideas for a space combat game in Lancer’s setting. And-

Condit: As an old Battlefleet Gothic hand, I’ve got to say, I was excited to see where this particular story is going, but-

Miguel: I was going to say, I was recalling my days of trying to get anyone else to play Battlefleet Gothic with me back in high school, so-

Condit: I’m glad I’m not the only one.

Miguel: Yeah, yeah. There’s at least two of us in the world.

Kai: And so the pitch went out, it was like, why don’t we do a naval combat game instead? Tom was too busy at the time to commit to an entire other game. So they reached out to me and said, hey, would you like to take on this project? And I said, yeah, because when somebody does that, you say yes. Whether or not you are panicking at the time going, I’ve never made a full-ass game before. What am I going to do? But I said yes. And that was what turned into Lancer: Battlegroup, which I refer to myself as co-designer because Miguel did have a lot to say about that. He provided the sort of skeletal starting point for the game systems. He wrote a lot of the background and a lot of the fluff and a lot of all of that other stuff. And I took it, and in the span of about 9 or 10 months, we did a very intensive set of playtest iterations.

I would do a new revision every month. I would put it up on the Discord and I would say, okay, here, go ahead, run through this, see what works and what doesn’t. Another month would roll around, I would get another set of revisions out. And so that launched, I believe it was late last year, and-

Miguel: That sounds right. Yeah.

Kai: It’s been pretty well-received, which I’m very pleased about. Everybody… It’s a game where I think it appeals to a very niche audience, but that audience really seems to like it, which is, in my opinion, a good place for games to be.

Condit: I’ll tell you, as what someone might call a spaceship fanatic, it’s always nice to see someone in that same kind of head space. And you do get a very devoted crowd to any kind of game like that.

Kai: Yes, yes, very much so. And then the latest project that I worked on, Tom reached out to me. He wanted to do some smaller releases for Lancer, something to just keep things going and maybe add some stuff to the game that had not been fully covered. And a big part of that was things like play modules, campaigns or adventures, what other RPGs would call those. And I had an idea for something along those lines to do a very straightforward pick-up-and-play thing for Lancer, because Wallflower is very well-received. People love it, it’s very good, but it’s also very dense and it has a lot of deep Lancer lore in it that can sometimes feel overwhelming for people who are just completely brand new to everything. It’s kind of getting thrown into the deep end. So I wanted to make something that was a little more straightforward and a little more easy for new players and new GMs alike.

And so that was Operation: Solstice Rain, which released earlier this year. And it’s just a very basic, straightforward, two-level mission module that starts people out from square one. It has maps, which is a thing that people are really interested in having, illustrated to show, okay, here’s what a good battle map for Lancer can look like. Here’s how much cover there is. We’re going to mess with elevation, terrain density, here’s where the enemies can come in. Here are enemy tactics for the GMs who have never played this game before, never run this game before. Here’s what you can do with this. And that has also been pretty well-received, which I’m very grateful for.

Condit: And full disclosure, I’m actually running Solstice Rain right now as an intro campaign for a group that actually includes some of our other contributors on the site. So Rocco, if you’re reading this, if you download that PDF, you’re off the team.

Kai: Well, that’s good. I hope you guys are enjoying it.

Miguel: Well, thank you for being spoiler free.

Condit: Yeah, we’ll come back to Solstice Rain in a bit. And Wallflower as well. I actually played through Wallflower as a player. And to your point about it having a lot of lore in there, when I was trying to figure out what I would run for this particular group, I read through the actual document for Wallflower and was like, dear God, there’s a lot of stuff in here that I just never even saw. So please take this as a positive thing, but it does kind of work in a similar way to those sort of BioWare CRPGs where you make the different decision and you can wind up seeing a completely different aspect of the game.

Kai: Yes. That has happened in a lot of players’ playthroughs.

Condit: So as we talk about Lancer a bit, I want to start with the actual story behind it, where humanity is in… what is it, 5,000 and change post-union?

Kai: 5016.

Miguel: 5016 in the endgame timeline, which I think if we mathed it out, I think we did this on the Discord a while back, is roughly the year… It’s like 15,000 years from now in real-life Earth years.

Kai: Yeah, it’s like pretty far future.

Condit: I tried to do that math myself, and I’m glad that I didn’t have to do it live, but I was close. So I think I had it at about 13 or 14 thousand.

I felt like it was perfectly fine and good to try and imagine a Future that is not foreclosedU pon.

Miguel: There’s some fuzzy math in Lancer. There’s a joke that we used to have when I would lead sort of vision on certain things that there’s a lot of “Miguel Math,” which is often up to interpretation and very, “I need an editor.” Not too good with math. So it might be worth double-checking those numbers. But if I recall correctly, I think Lancer is set 15,000 years in the future, which in the in-game dating system is the year the Core Book is 5016 U, which is 5,016 years after the Foundation of Union.

Condit: And one of the things that I wanted to start with is the theme and the general vibes, because it does have a sort of, I don’t want to say unique, because there is definitely a lot of great science fiction out there that has a similar, optimistic, “we can build better” theme. But when you look at things that really break into the public consciousness, there’s a lot of things… A lot of it seems to be, the small group of heroes struggling against the undefeatable, hegemonic power, where what I was really struck by in reading the “Brief History of Union” bit, talking about the three traumas that led to the foundation of Union.

And that third one being, you switch on the receivers and there’s all this radio traffic or other communication saying, we need help, help us. And humanity, in your telling of it, has a response that is completely different to what I think you would expect to see in most RPGs, which is, why don’t we help them? Let’s give them what they need. And one of the initial questions is, from a fundamental perspective, how do you square that fundamentally optimistic view on humanity with everything going on in the world that we’re in right now?

Miguel: How do I square that? To give into despair is to admit defeat. Lancer came from a point of deep frustration. When I was first writing the narrative components of it, I was waiting tables post-grad school, not making a ton of money, getting a lot of assistance from the state, that kind of stuff. And just being very frustrated with that sense of really just kind of grim inevitability about the future, which unfortunately hasn’t changed and has only kind of gotten worse. But I felt like, as a fiction writer and someone who liked writing speculative fiction and liked growing up reading speculative fiction, that it was perfectly fine and good to try and imagine a future that is not foreclosed upon.

And I think Lancer was… Like I grew up playing 40K and I’m very used to modern science fiction, imagining any potential humanity as one being that is fascistic and craven and power-hungry or sees humanity as something that is mandated to be this kind of chauvinistic, expansive force where there is one view of the future that is typically white and western. And in setting out to write Lancer, I kind of wanted to write my response to it, which was like, it doesn’t have to be that. And it was certainly an impulse that I think and a lot of other people feel, before it gets ground out of us or just numbed by the difficulty of the conditions that we all live under today. But when you hear someone calling for help, you want to help them, right?

And that was the 0.1 or the zero point or whatever we want to call the origin of, okay, let’s write up a science fiction setting that is grand in scope and scale, full of mystery and has that initial… Imagines the future where humanity acts on that impulse of someone’s crying out for help and you do that. That is, as I discovered as Lancer hit more folks than just myself and Tom, a really complicated proposition and sort of a complicated thing that winds up sometimes that help is not… That impulse outs in ways that can hurt or be self-serving, right?

Condit: That the person giving the help doesn’t necessarily listen to what’s actually needed.

Miguel: They give the help that… Exactly, they’re not listening to what’s needed and they give the help that they think is needed. And I think that sort of working out what the proper way, and I don’t have an answer to that, obviously, and I would hope that upon reading Lancer and digging into the lore, folks also realize that Union doesn’t have an answer for that. And doesn’t have an answer to that to the point that it’s torn itself down twice now and is in sort of a coin-flip moment and then torn itself down and rebuilt it. It’s on the third committee and is approaching sort of a coin-flip moment in its present iteration. But yeah, sorry, I’m rambling a little bit. And Kai, if you want to jump in at any point after, please feel free, I don’t want to dominate this conversation, because you are a writer of this as well.

Kai: Well, everything you’ve said, that’s basically how I view it. And from my perspective, I am a very, very cynical person. Anybody who’s had the misfortune to read my Twitter account or other social media postings, you’ll be able to tell that I am not overflowing with optimism. But even still, I cannot deny, and I will admit there is good in the world. It is not just hopeless, it’s not all doom and gloom. There are people out there who do good. And I think that it is extremely valid and relevant for a game like Lancer to take up the position of, okay, what if we focus on this kind of element rather than the usual expectations of crumbling space empires and space fascists and all that stuff. Everybody, there seems to be a deeply seeded impulse in not just games, but in a lot of media to try and find the hidden twist where everything is shittier.

It’s like, okay, these guys say they’re good, but what if they’re actually evil, what if there’s actually like a sinister conspiracy going on. It’s the JRPG thing, you see a church in a JRPG thing, they’re evil, they’re a hundred percent… They’re going to summon a fucked-up god, and that’s going to be the final boss. And you’re going to have to fight that guy. And I think it’s more interesting to have a setting where you have a major faction, like Union, which is flawed, but well-meaning. There is no sinister conspiracy. It’s just people, it’s everybody trying to do their thing, and sometimes they do not do it well, or they do not do it perfectly, but there isn’t just some, well, this is all a deep state conspiracy to brainwash everybody, take over the universe, that kind of thing.

Condit: And obviously, Lancer is not a setting where these sorts of awful factions don’t exist. I mean, you’ve got the Harrison Armory, which is about as close from my reading as you can get to the 40K Imperium in your setting. You’ve got the Trade Baronies, which are what if the various warring factions in Dune cared even more about money?

Kai: Harrison Armory is a very interesting one because a lot of people look at that and they immediately go, oh, okay, these guys must be the evil space Nazis. And it’s like, okay, well, they’re kind of descended from that. But my read on Harrison Armory has always been much more, this is America. This is the United States of America in its most idealized, well-realized format. These guys actually have a robust social safety net. They have infrastructure that doesn’t suck. They have all these great things that America says it has and regularly fails to deliver on. They are an uncynical version of the American success story, and yet it is still built on the back of imperialistic, colonialistic expansion. And so-

The question that Harrison Armory asks is, if you had a nation that did all these good things where meritocracy was not just a cynical ploy, but an actual real thing and they took care of you and your kids, would that still justify the means to those ends?

Miguel: I’m glad you said that because that’s exactly how I was imagining them when I started writing them. It’s like what if it’s America, but it’s America perfected.

Kai: And it-

Miguel: It’s not necessarily a good thing,

Kai: Right, no.

Miguel: For everyone else.

Condit: Depending on whose interpretation of America, for sure. Yeah. Without getting completely derailed here, we could talk about that and fill an entirely separate interview. But yeah, it’s a fascinating approach.

Kai: And the question that Harrison Armory asks is, if you had a nation, if you had a state that did all these good things where meritocracy was not just a cynical ploy, but an actual real thing and they took care of you and your kids, would that still justify the means to those ends? Would it be okay to do colonialism if you could actually get all the cool things that were supposed to be promised from that? And the answer is, well, no, not really. That’s still colonialism, that still sucks. They are still coming into your world and they are going to say, okay, this culture of yours is neat, but what if we made it more like ours? What if we gave your kids our education instead, and you guys got to celebrate our holidays and you worked towards our ends? Oh, we’ll take care of you. It’s fine. Don’t worry about it. But we’re still going to do that.

Miguel: Yeah. I think one of the things that—and thanks for phrasing it like this with questions—one of the things that guided the early writing of Lancer was I imagined it as a setting that it doesn’t have a lot of answers. It has sort of a ton of core questions. I also contend with it being an optimistic view. An optimistic view for me is like Star Trek, in contrast to a pessimistic view, which is 40K and many others. Not that it’s a bad thing. But Lancer as a game, as a setting, asks, I think, a ton of questions that we hope players and readers can go on to answer. Obviously, we have a perspective when we’re writing these questions just as, to use Harrison Armory as an example, I wrote that sort of imagining what does the perfect America look like. And you can see my and Tom’s perspective on that answer. But I’m focusing on the sort of original core of your question, which was like, why do we think people liked it?

Condit: To go back a second to the optimism thing, my conception there, when I say it’s optimistic, is that your view of humanity seems to be a bit more optimistic than, and pardon me, I was a philosophy degree in undergrad, so I’m getting a little bit too much into my own bullshit here, but there’s this question of what is the fundamental essence of humanity? Is it the kind of Hobbesian war of all against all, or are we fundamentally capable of something that could be recognized as good, which is, philosophically at least, an optimistic view on humanity? And the outcome that you write about in Lancer may not be the greatest one, but the view that, at the very least, the people in 5016 are trying, is one that seems a bit more on the brighter side of things than it could be, if that makes sense.

Miguel: Yeah. And I’ve definitely used optimistic to describe the setting of Lancer. I think a lot of that comes from, and I wish I had a theory vocabulary ready to go, but I think for a lot of the core assumptions around humanity in Lancer, I wanted to imagine a future that, like I’ve said before, a future that is not foreclosed upon. I think we all are interpolated through and live under capitalism and it’s pretty fucking… Sorry for swearing, but pretty grim and competitive and imagines humanity as small and scared and a collection of alienated, selfish individuals.

Kai: Yes. Atomized. That’s the big thing.

Condit: I want to be clear, before we go on, if I censor anything from that sentence, it’s going to be your apology for swearing, not the actual swearing.

Miguel: [laughs] I appreciate that. So I felt that. I was working a horrible series of jobs for way little pay and for not a lot of money at all, and struggling, sort of imagining if we have all of these global scale climate change and multipolar futures, sort of existential threats, wondering, there’s all that, then all the way down to how am I going to pay rent? Where does healthcare come from? And realizing, all of those things make people really afraid and fear makes people selfish.

And the systems that create those conditions are built by people. So the not optimistic part of Lancer is like, yeah, what we have right now, crumbles, falls apart, the global population falls to 500,000 people and it’s GGs, right? But humanity doesn’t die. We get a bit of a reset and we build from there, sort of imagining a different way that is not one where we are from birth pitted against each other in just merciless competition to grab as many resources as we can and be on top and never actually get that feeling of being on top and never actually get that feeling of being satiated.

So if there’s an optimism in Lancer, it comes from imagining a humanity where those are no longer first principles. And that stems from creation, the human creation of systems that ensure everyone has basic needs met. Because no one wants to be cold on a winter’s night. No one wants to be hungry. And the easiest, best, and safest way to do that is to work together, to have someone watching your back when you can do that. And that is… Daily existence in the real world is deeply frustrating. And it’s the most pollyannish, most optimistic thing that I can imagine is, well, not if everything’s fixed, but what if everyone is working together to fix it? And that was kind of… That’s the start of Lancer, I think, is at least the start of the setting. Obviously, complications ensue and spiral from there. But yeah. So yes, I guess you’re right. I concede, it is optimistic.

Kai: And just to add my own perspective to that, I will say that it is difficult to sometimes find the right vocabulary to discuss things, especially when people are so often trying to summarize it. And I find this is a thing that kind of trips up a lot of discussion of games, not just in terms of narrative, but also in terms of design, when people talk about a game that’s crunchy, it’s like, well, what is crunchy? What is a rules-heavy game? Is there an official measurement of weight for that? And I feel like the same pitfall happens when you’re trying to discuss tones and themes. Is Lancer an optimistic game? Yes, but also there are elements of it which are not. There are megacorporations. Capitalism has not truly been eliminated. There are people who believe in terrible things and who do horrible things. And it’s like a lot of times there’s a lot of very spirited argument and discussion that kind of centers around, well, Lancer bills itself as optimistic, but it isn’t really optimistic because this is in the game, that is in the game.

It feels difficult sometimes to try and put a tagline or a brief summary to something that has, I would say, more depth and nuance to it than just, oh yes, this is an optimistic game.

Condit: Oh yeah, for sure. And I agree with you there, but I think also the idea of having a game where if you are playing as an agent of the Union Department of Justice and Human Rights, right? This is one of the biggest players in the galactic scene. And to have the full weight of the galactic hegemon being behind you when you say, hey, stop violating those people’s rights.

No one wants to be cold on a winter’s night. No one wants to be hungry. And the easiest, best, and safest way to do that is to work together, to have someone watching your back when you can do that.

Kai: Yes. Yeah.

Condit: Kind of an inversion of what you would typically expect the hegemon to be doing.

Kai: Sure. No, I absolutely agree. But I bring this up because there’s always a lot of arguments where people are coming in and are going, well, this doesn’t seem particularly as optimistic as I would’ve expected, or why does Union let this other stuff happen? Why doesn’t Union just do something about it? The main answer, just from a top-down perspective is because if there wasn’t anything wrong in the setting, there wouldn’t really be a game to have.

Condit: What’s the point of robots the size of buildings with weapons that can demolish things if there’s not a good villain to point them at?

Kai: Right. And this is a thing that I have noticed that sometimes trips in people up before, which is they look at all the description of Union and it’s like, well, I don’t understand. What am I supposed to do within this setting where people’s basic needs are met? Nobody really seems to have a whole lot of major conflicts going on. And it’s like, well, that’s what everything else is for. You’re not usually playing Lancer in the middle of the part of the setting where things are more or less okay, you are playing it in parts of the setting where things are not okay or not as okay.

Condit: It’s the bit in the Core rules that talks about, and I’m blanking on the actual language here, but the idea that Union’s next victory is kind of at the margins of its geographic space where the core is basically there and they’re spreading it, not quite at the barrel of a gun in the same way that some of the other powers are trying to, but essentially saying, hey, we’ve got this wonderful stuff. If you would like to join us, here’s our card. Call us.

Miguel: Yeah. That’s why the timeline is so long too. I think it’d be a much more compressed timeline if it was entirely at the barrel of a gun. So the positioning of the setting is imagining the Union exists in its third iteration, the Third Committee, which is it’s expanding, but it’s expanding slower than its predecessor, the Second Committee, which was very much, in the fiction of the game, we call it anthro-chauvinist, right? It is sort of that, if you remember old forum posts from 2007, it’s very “Humanity, Fuck Yeah!” where it imagines itself the true and correct and just way. But the way to look at the ideology is that it’s created by the conditions that it was born in, which is like, we are small and scared and we are a single planet and we could hear everyone calling out for help and we never ever want to have that happen again. And we’ll accomplish that by any means necessary.

So in the fictional setting that has crumbled, the Third Committee has risen, and now it’s expanding again out from sort of a contraction. So as players, you are at the advancing edge. Ideally, this is where we imagine most games take place, is at the advancing edge of that re-expansion into territory that has already been settled some years in the past, centuries in the past, whatever, or at the very bleeding edge of it. We probably could have done a better job explaining that in the Core Book. [laughs]

I think that writing that was a learning experience for me because I’d come from just narrative fiction and never writing for games or anything like that. So positioning the player and to see those questions and head them off of, well, what the fuck do I play for if the core is post-scarcity and everyone’s needs are met and it seems pretty great. And we didn’t even have a money system. It’s a core thing for RPGs is gold. You have your money system in the game. We didn’t have that until we came out with, I believe, the Long Rim expansion.

Kai: Yeah. The Long Rim had the Manna system.

Miguel: Yeah. So that expansion is happening and we sort of imagined sticking the player at the breaking point of all those waves as Union is re-expanding out into its old territories that the Second Committee first established and in new areas that they have not yet been. And they are the galactic hegemony but that doesn’t mean that other constructions of humanity don’t exist out there. That’s like what the Aun are, which is a civilization outside of Union.

Condit: And tying into Solstice Rain, I think that the civilization you run into there is something similar as well.

Kai: Yeah. Solstice Rain is interesting because the setting there was a planet that was originally settled by the Second Committee. They were just in the very early stages of colonization. When the Second Committee collapsed, there was a revolution in the wake of the Hercynian Crisis, which is the war that was talked about in No Room for a Wallflower. The Second Committee started out very, very hands-off in terms of, let’s just say the atrocities they were responsible for. Their big first act in taking power was launching a series of kinetic kill-rods called PISTON-1 at the Aun.

And that was a very hands-off, remote, blood-is-not-on-our-hands kind of deal, but it was still committing genocide. They basically threw this out there. It was going to take centuries to impact. And they did it because, as Miguel said, the Second Committee’s driving motivation was basically fear. They saw the Aun as potentially a competitor, eventually maybe somebody who was going to come and try to attack them and take the reins of humanity for themselves. So the Second Committee started out that way, a very bloodless and dispassionate sort of thing. And then by the time of the Hercynian Crisis, our hands are soaked in blood. We are literally going down to this planet and centimeter by centimeter we are destroying the biosphere, we are burning it with flamethrowers, we are scouring it with radiation. And the whole thing collapsed at that point.

Everybody saw this, they were horrified. The soldiers on the ground were horrified. It was just the end of everything. And Cressidium, the planet in Solstice Rain, had just been getting colonized when all of this happened and a bunch of people fleeing the collapse ran there and then shut the door behind them, and they self-imposed a blanket isolation. They figured that the collapse of the Second Committee meant that Union was done. And everything after that was going to be like feuding, warlord states, the post-apocalypse scenario was going to happen.

They figured it was going to turn into 40K and they were like, okay, no, we’re just going to come here. We’re going to shut the door behind us. We’re going to throw away the key, shut off all communications, go dark. And then, yeah, 500 years later, Union is just kind of out there exploring and seeing what’s going on. And they run across a planet that has developed an entire society that has five centuries of history behind it who thought that Union was done. And they’re completely surprised to find out that no, actually, Union is still around. Like, hey, what’s going on? You guys want to come back and do the thing again?

Condit: Hopefully with a better result this time.

Kai: Hopefully with a better result this time. And Solstice Rain does kind of explore the legacy of that a little bit because everybody on that planet is in some respect a descendant of the Second Committee. Some of the nations on that planet have clung to those anthro-chauvinist ideals a little more strongly than others.

Condit: It kind of struck me reading it. It’s an opportunity for the players and through them Union itself to kind of reckon with the sins of the father, so to speak. The goal that you are chasing here in Solstice Rain, and I don’t want to spoil too much of it for anyone who might be interested in playing it, but the goal is pretty clearly stated from the start that not only are you trying to do what you’d normally be doing in this sort of recontact situation, but you’re also trying to prove that the anthro-chauvinist, or to use the modern equivalent, the fascist worldview that they had is illegitimate. And that we can win this, not only with our ideology but through our chosen means.

Kai: It was very important to me that Solstice Rain, being a mission module that was meant to kind of ground new players and new GMs in the setting, and the position it takes as a default is that you are Union pilots because it’s a pre-made module. You kind of have to stick with something. You can’t be wishy-washy with those. You can’t be like, well, you can be whatever. It’s like, no, if somebody’s going to pick this up and play it, just bring it to the table and go, you have to give them a default position. So I went with Union because it is the game’s iconic faction that you are most likely to be playing in and around. And it was important to me that the start of Solstice Rain was a diplomacy mission. That you are actually not just going in with the aim of fighting, but you are there as part of an ambassadorial delegation.

Things happen, obviously, that force your hand; it’s a game about mech combat, so that’s got to happen somewhere in there. But I wanted it to not just be a case of you’re being dropped onto this planet because they need fighting, go. I wanted to frame it in a way that shows here is an example of what might bring players out into the far reaches of space, into these uncharted, less explored areas, and what that might look like. And for me, it was important to set things so that there’s an idea that you can go and do stuff, but it doesn’t have to just be you’re getting sent to go do war. You can get swept up in it, but you don’t have to just be going and saying, all right, we’re going to fight these guys.

Condit: Yeah. And the idea that from the start of reading through it is that the player should feel like this is the last resort, that all diplomatic measures have failed. This is not a major power that comes in swinging its guns around.

Kai: Exactly. That’s exactly it. It is impossible to escape the fact that Union is a big power that has military force behind it. But at the same time, I don’t feel like it does the setting any justice to have this module start with “Union shows up uninvited and starts swinging its guns around.” Instead, it’s “Union shows up and they want to say, hey, would you like to join us?” And there are diplomatic meetings and they’re even including the Vestan Sovereignty who are the anthro-chauvinist holdouts in this. They’re including them in these meetings too.

They would be happy to have them join the fold—obviously, they would want them to abide by the three pillars and not be huge assholes about it—but they’re not going, ah, you guys, you have to get out. Fuck off. We don’t want you. They’re like, no, we would be happy to bring you to the table. What can we do to resolve this situation so that everybody comes away happy? And then once that diplomacy breaks down, once things go off the rails, then it becomes necessary. But only at that point does it become necessary to say, okay, now we have to use force.

Condit: Yeah, I mean, to me, and the kind of Union ethos seems almost like, to fall back on a well-worn nerd crutch here, but kind of like the grownup version of Spider-Man’s maxim, that with great power comes great responsibility, but sometimes it’s important to recognize that that responsibility often entails not wielding the power. Sometimes your biggest job as the person who’s the adult in the room, so to speak, is to facilitate rather than to impose.

Kai: And it is kind of funny because, like I mentioned earlier, there are sometimes a lot of heated discussions and debates around why doesn’t Union do something about-

Miguel: Harrison Armory?

Kai: Yeah. Why do they let Harrison Armory exist? Why do they let IPS-N exist? IPS-N is like the closest Lancer has to a pure cyberpunk mega-corporation. Of all the corpro-states, they are the least state-like. They basically just exist to make money. They sell guns to anybody who can afford it, and they have a monopoly on interstellar travel. Union has the blink gates, which are the big, faster-than-light transit points, but anything that isn’t connected by a blink gate, you have to use a regular ship to go from point A to point B. IPS-N basically has a monopoly on that.

So this private corporation has all this power. They use it to make money and do shitty capitalistic things. It’s like, why doesn’t Union do something? And it’s like, okay, what does doing something about this look like? What do you want Union to do? Do you want them to go to war with IPS-N? Do you want them to bring out all the navy ships and get into a shooting match? Would that make things better or would it just make things a hell of a lot worse? Because now you’ve killed a bunch of people, first of all, you have probably massively disrupted interstellar trade for millions and billions of people. That’s going to have huge knock-on effects.

What should they do then? What is the actual answer you want? And in Union’s case, the way to fight something like IPS-N would probably be to work to undermine their monopoly, create alternatives, better infrastructure. But that’s the sort of thing that’s going to take a lot of time. It is not going to give the visceral satisfaction of beating the bad guy. And in the meantime, you kind of have to let IPSN exist because you don’t have an answer to that that does not involve running out the guns. And Union does not want to do that. So it is kind of funny that this comes up a lot. Why doesn’t Union wield this tremendous power they have? And you got it exactly right. Because doing that would be awful. It would be a terrible outcome for everybody.

Union’s superpower in the setting is they are strong enough that they could probably win any war once. They have a huge amount of naval firepower, they have a huge amount of military might, and they could probably win a war once. And then after that, they would be in tatters. Whoever they fought would be in tatters and then somebody else would come in and go, oh, this looks like a great chance for me to sweep up the pieces. And now you have the Karrakin Trade Baronies in control of everything for the next 5,000 years or Harrison Armory or somebody else and you have billions of debt, et cetera. It’s a bad situation.

Miguel: Yeah, I think that there’s this libidinal desire for violence and great war in big settings like this. Everyone loves to see, and Battlegroup touches on this as well, the big fleets banging away at each other. But something like that marks the failure of Union’s ideology and entire project, even if they were to win. Congrats. You are the king of the ashes now, right? You’ve affected another collapse to the point of your goal. It does not matter whether you win or lose because you’ve lost as soon as the big guns open up, basically. A lot of folks asking the question of, well, why don’t they fix this? Why don’t they do this? Some of the setting, most of the setting, actually, it is our intent for those questions to come up, for people to look at the contradictions in the system that Union has because it’s not a perfect system. It shouldn’t be.

We’ve talked about it as being utopian. We’ve gotten dinged for that, which is fair. But part of that is just marketing language. But it is not intended to be a utopia. It’s not intended to be a perfected project. It’s intended to be one that is currently in the making. And if you as a player look at these systems like IPS-N, or look at the Karrakin Trade Baronies, look at Smith-Shimano, look at any situation where the Core Book says something and then a scenario or a lore entry or something in the Core Book or in something else says, here’s the contradiction to that. Here are flash-grown clones that are stuck in mines and never escape, that they are never allowed out to see the sun. Or just the title of kings and emperors of worlds. You look at this and you’re like, hang on, Union is supposed to be better than this. Why aren’t they fixing it? I think Kai just ran you through a very good example at a very high level of why they’re not fixing it. But a lot of that is also: that is precisely for you and your playgroup to answer at the table as a crew of Lancers doing their small parts in a much grander moment in history.

Utopia is a verb. It is not a finished product. It is a thing you continuously strive for.

Kai: The only thing I would add to that is even in the Core Book in-setting, this is an argument people have. The major coalitions of the Third Committee, it’s not a unified body. There are different parties within Union, some of whom are like, no, we should be taking the revolution to these worlds. We should be out there and we should be doing things way more actively. And then there are other factions that are like, that does not seem like a wise course of action. We should take things a little more slowly and a little more conservatively. Small-c conservative, I’m not talking the American vision of Conservatism, which these days is just screaming fascism.

But they’re more reluctant to commit to these large, big, hands-on interventions because, you know, you could argue because they’re worried about repeating the sins of the past, or you could argue because they have grown comfortable with their position and they’re maybe a little too sedentary. But even within the setting, this is an argument that is had within Union: how fast and how hard should we be pushing our vision of the future and in which ways should we be doing so? Even within the game, there are no set answers to any of this.

Condit: And I think that kind of goes to something that Miguel had brought up, which is that this is not intended to be a finished product. It’s a human endeavor that’s built by and built upon the work and labor of humans. And by its very nature, yeah, it’s not going to be perfect. There’s going to be contradictions. We’re all flawed and contradictory beings as much as we try otherwise.

Kai: The phrase that crops up on the Discord server a lot is that utopia is a verb. It is not a finished product. It is a thing you continuously strive for.

Condit: All right, so I want to move before I take up way too much of your evening here. I want to talk a bit about the actual mechanics of the game a bit. Our main beat on Goonhammer is obviously tabletop war gaming. We cut our teeth on 40K and those sorts of games. And this week’s coverage has been largely focused on, I say has been, will be largely focused on mechs and mech-related properties, so I do want to talk a bit about the actual game. Obviously, I think for anyone who’s played fourth edition Dungeons and Dragons, there’s going to be some glaring similarities there just in the combat on a grid, the action economy is very similar.

And my experience at least having mostly lurked, posted a bit on Something Awful back in the day, there was almost a wall between in the Traditional Games subforum, with the RPG posters on one side and the wargaming posters on the other and never the two shall meet. But to there’s a lot of elements in Lancer’s combat that seem to be taking inspiration from the sorts of tabletop war games that I’m more used to. I’ve looked particularly at the way that the SitReps [Lancer’s suggested encounter designs] are laid out in the core rules: you have objectives that you’re holding.

So to start out, what’s your pitch to someone who is a majority war gaming player, why they should give Lancer a shot?

Miguel: I’m going to let Kai take this one because my pitch is mostly a joke—and sorry for the prefacing because it’s not going to make it any funnier—but it’s way cheaper than playing 40K.

Kai: Well, I agree with Miguel. Holy shit, absolutely. You can play Lancer on the back of-

Miguel: You can play for free.

Kai: Yeah. But to go back to what you’re saying, in terms of specifics, you brought up sitreps and everything and I think that’s definitely a huge selling point in terms of what about this might appeal to somebody who comes from a more tactical war gaming background where fights in Lancer, and you also see this in the other game that Tom is currently working on right now called ICON, which is a more fantasy tactics game that’s got a lot of Fire Emblem and Final Fantasy Tactics influence. He does it there too, which is that fights are often about more than just killing the other guy. You have that, you have combat, but the best sorts of missions in Lancer will have objectives going on beyond that, that force you to respond to the situation in ways that are not just optimizing your damage output, ways that are not just about getting in a gunline and shooting people, but from a more sort of top-down pitch.

I would say the thing that I would sell somebody on Lancer, if that was my goal, to find somebody who is more of a war gaming bent and pitch Lancer to them, I would say the thing that probably helps the most is that Lancer has a very clear and very explicitly spelled out separation between the mechanical and the narrative layer. In games like Dungeons and Dragons, not every edition of D&D has done it to this extent, but there is a much more, if I were going to be generous, I would say fluid line, if I were going to be less generous, I would say muddy line between the narrative and the mechanical to the point that you would get arguments over, well, what does it mean when this spell says it ignites flammable objects or whatever. What is a flammable object? What does this mean?

You get into lots of arguments about naturalistic language or about how blurry should the line between the narrative and the mechanical be, and Lancer says that you can have a game that has narrative play and that has tactical combat play, and you can actually draw a dividing line between them and you can say that one does not necessarily overlap with the other. So when you are in the combat layer, that’s what you’re focusing on at that moment, and you don’t have to concern yourself with the narrative layer as strongly. Obviously, there can be roleplaying in the middle of a fight, you can have and you should have cool narrative moments, but it isn’t a case of things getting blurry and overlapping. You can just focus on that in the moment and when that moment is done, then you can pull back and zoom out and now you can focus on the narrative and you can do that without worrying about how it’s going to affect your upcoming combat performance.

There is nothing where it’s like, well, do I put my points into pilot mech better or learning a language? Lancer says, no, fuck that. Everybody’s a mech pilot. You know how to do this shit. You will never make a decision for your character’s narrative, for your character’s background or personality, or what skills they know or where they come from that will ever make you suck more when it comes to the actual fighting. Those choices are broken apart and separated for a reason, which is that it really sucks to make a decision that you think is cool in the moment for role-playing purposes that bites you in the ass when it comes time to shoot a gun. And I think that that would probably be my pitch for somebody who is big into the tactical war gaming scene because my guess is those guys probably don’t like having to make those kinds of decisions that a lot of role-playing games ask you to do.

This is a thing you see in an RPG like Shadowrun, which after so many additions eventually started just straight up giving you a separate pool of skills that was for things like learning languages and hobbies and personality stuff because they realized that players were being forced to choose between the skills that would make them better at being cyber mercenary criminals or having a fleshed out personality.

Condit: Yeah. It’s kind of the idea that when you show up to the fight, the only decisions that are going to hold you back there are the ones that you intended to make to do that. You’re not going to be forced by some other decision outside of that.

Kai: Exactly. The decisions that you made narratively for your character, the background that you chose for them, their likes and their personality, that does not have to interfere with your tactical decisions or the ability of the mech build that you make. That is on a whole separate level. And if you are more into that level than the other, you can play Lancer and be perfectly fine. And if you love to role-play and get really deep into the narrative, you can do that and it won’t make you worse when it comes to fighting. And I think for me, that’s a big selling point for people who enjoy the tactical war game side of things because it means they can really indulge in that part of it without compromising the other elements of the game or the other elements of the game compromising their ability to engage with that.

Condit: As far as the narrative side goes, when I was sort of gathering notes and stuff and preparing for this, one of the comments that had come back from some folks who were more on the TTRPG side of things from looking at some of the narrative rules and mechanics in the Core Book, they seem a bit less defined, but I think that’s been picked up a bit in some of the recent supplements, like the bond system in the Karrakin Trade Barons. I wanted to kind of talk a bit about where that came from and how that developed and that sort of thing as well.

Kai: Yeah. That’s one of those things that unfortunately I think Tom would be in a better position to answer. I will say that he is a big fan of games like Blades in the Dark and that things like that and Powered by the Apocalypse, it had an influence on his design. And I feel that bonds are a way to incorporate some of the tech from games like that into Lancer a bit. I will say from my perspective, I’ve always felt it’s kind of funny to look at Lancer just out of the core book and people have done that before. They’ve been like, well, the narrative rules and everything seem pretty ill defined. But then if you go and you look at a game like Dungeons and Dragons, most of the time when it comes to narrative rules, it’s, well, make a skill check.

Did you pass? Okay, well then a thing happens. Did you fail? Well then it didn’t happen. And not that much different from how Lancer kind of handles, well, okay, you’re doing something during downtime, you’re doing something in the narrative. Roll a trigger. Did you hit this number? Okay, something happens. Did you hit this number? It kind of happens with a twist. Did you roll this number? Well, there’s a complication. So from my perspective, it’s not too dissimilar from what a lot of RPGs do already. The only thing that Lancer does that’s really different is just draw a much harder line between when you will do that versus when you will focus on the fighting.

Condit: Yeah, that’s fair. I think a lot of that may be informed by that line of distinction where you’re looking at the tactical combat. It’s immediately clear that there was a ton of playtest and balance work that went into those, and there’s just so many rules there that just comparing how many rules there are compared to the narrative rules might be a large part of that.

But I do also want to talk about the Karrakin Trade Baronies supplement a bit from the narrative side of things. I know we touched on who the Baronies are specifically, or really more generally, but the flashpoint in there, and I’m blanking on the name of the world that it is because I don’t have it in front of me. Let me grab that real quick.

Miguel: Is that the Dawnline Shore or is that the one that’s in Battlegroup?

Kai: The Dawnline Shore is in Battlegroup.

Condit: Yeah. This is Sanjak.

Miguel: Sanjak. Yeah.

Condit: Ludra’s World. Yeah. This is part of what you were talking about earlier, talking about the flash-clones that are held underground and not permitted to see daylight and that sort of thing. And there’s this character in there that has a lot of in-character writings included, Tyrannocleave, that have sort of a revolutionary Latin American feel to some of the invective that’s going on there. Can you talk a bit about the inspiration for this particular flashpoint? What’s going on? What brought it to the page, so to speak?

Miguel: The creation of the Baronies is an interesting thing. That was one where Tom and I were collaborating relatively closely, sort of asynchronously corresponding and writing one another. Because we’d sorted out the corpro-states and we kind of wanted a different entity in there. One that could be less of a subsidiary of Union, or less of a client of Union and more of something that is like, these guys could rival them. They’re a sizable enclave in there. So we just on the aesthetics of it, both thought it would be a cool thing to have in there. Let’s have a collection of noble houses that have persisted for thousands of years. They, like the people who had gone on to found Union, were present before the collapse. I think they can in some way legitimately claim the mantle that they are the descendants of humanity, right?

There’s no break point like there was for union. They departed Cradle (what we call Earth) on a generation ship and arrived at their planet, Karrakis, is what it’s called now, settled it and have had basically an unbroken line of history through there. That of course means that they came over to Karrakis without that fundamental reset. They experience it to a degree when Cradle goes dark and they have the last transmissions and they realize like, okay, we are taking over for humanity. We are continuing this project forward.

They didn’t really have that same reset that Union has. That moment of Union, one of the core traumas that Union experiences is thinking that they’re the first people on earth and they discover that they’re not, right. They’re actually post-apocalyptic survivors of our system that we live under today. But Karrakis never collapsed. They have survived for 15,000 years and have only progressed further with the same inequities and glories and greeds and everything that we have today.

We imagined them and their current system existing in sort of a network of guilds, more or less, that specialize in different industries. One of those was extractive industries, extracting, mining, extracting resources without the same sort of humanitarian impulse that union has. The value of a person in Karrakis and especially one in a noble system is much more instrumentalized. The individual is not valued. So they exist in a system that makes it easy for them to pump out workers as needed and treat them as cheaper to maintain than robots.

The situation in the flashpoint there on Ludra’s World is, yeah, I mean, I think you correctly identified it. It’s very heavily inspired by American adventurism and imperialism in Central and South America and the sort of imposition of everything from plantation labor on sugar canes to just industrial exploitation of native resources and the people who are unfortunate enough to be forced to work there.

So just starting from looking at history and currently active systems in our world, imagining—and I mean, this is pretty standard science fiction stuff—imagining a science fiction interpretation of that and imagining what a revolutionary movement that strikes a lot of similar tones as ones that have existed in the last 30 or 40 years here, what that might look like in this setting. I don’t want to be reductive, but that was the basic starting point for that. And then growing out from there was sort of combining everything that we’d written for how Union operates and everything that we’ve written for how the Trade Baronies operate, and seeing how those two systems collide in precisely a scenario that one imagines Union would step in, right. Writing out the history of that moment and examining, I’m rambling a bit, so please edit me down for concision, but imagining one of those scenarios where someone’s like, well, why doesn’t Union step in and showing, I think, what we think one of our answers to that question could potentially be. Imagining scenarios like this occurring around the galaxy or around the Orion or-

Condit: Yeah, I mean, because it’s a complicated situation even in the—

Miguel: Yeah. It’s a fucking mess. And it’s a mess with no good solution, really. That’s something that I remember getting pinged on the discord about people being mad at me for writing in that the Free Sanjak revolutionaries were executing families and of people who they believed or who economically dominated them. And it’s like, yeah, it sucks. There’s no easy answer. As much as we strive to answer anything in Lancer, that is one of the answers that you see. It’s like, the situation changed and it was brutal and awful for a lot of people before. And the process of, in this case, throwing off the fetters of a domineering monarch that is turning people into, treating people as disposable units in his mines—

Condit: Essentially entries on the balance sheet.

Miguel: Yeah. There’s no way that that’s going to be resolved without violence. And there is no peaceful resolution to that because one party has already stripped the other of any humanity and any dignity, right? And the only way that oppressed group is going to get it back is by killing a lot of people. And in this case, and that’s not the answer that we imagine for everywhere in this setting, but that was one answer here. And a lot of the reason behind that was because the Baronies are directly descended from us today, with all the baggage that that carries.

Tyrranocleave was heavily inspired by Subcomandante Marcos of the EZLN. He’s a revolutionary in southern Mexico.

Condit: Yeah, I was struck by one of the lines that, and I’ve got the page open. “We’ve talked at length with some of those young Union boys from the new solidarity. …Send the good ones to us (and have them bring some smokes!), we’ll train them smart and teach them who to shoot first.” I knew I had read something with a similar feel somewhere before.

Miguel: Yeah, I’m not sure if that is, but that was definitely at the time I was reading, what’s the book called? It was a book sort of, of Subcomandante Marcos’s collective writing. So I tried to not write one-to-one, because obviously I don’t want to imagine this is anywhere near as important or worth capturing that language. I don’t want to re-appropriate that language, but I wrote this character inspired by that movement and that person. And I wrote that character and that scenario as one potential answer to that sort of very general question of why are these bad things still allowed to exist in this setting that otherwise claims to be utopian? What happens when one seeks to address the contradictions in this setting?

Obviously, we imagine that Union is doing efforts like this and they’re either assisted by or guided by their efforts like this all across the galaxy as Union encounters the vestiges of the Second Committee. But for this one, it’s a flashpoint. There needs to be, for all of the complex and navel-gazy political and ideological things that Lancer clings to, it is a game about mechs shooting each other. And so this one is unfortunately an example of a violent resolution or a violent answer to that question of what is to be done, I guess. And like I said, I base it off of my interest in South and Central America in the sixties, seventies and eighties, nineties, and today. My dad is Nicaraguan. He has direct personal experience of Nicaragua in the seventies and eighties, the Contras, the Sandinistas, that whole thing. So I probably started writing that after talking with him, and it felt like a way to write through my feelings of it and my interests at the time as well.

Condit: So as you said, this is a game about mech combat. And before I do waste the entire rest of your evening here, I want to talk about some of the mechs. And I know that there’s a lot of them, there’s a lot of rules on them, but one of the questions that I’ve had pegged for this interview from the moment that we booked it is: of the mechs that you’ve written into this game, which is your mech? If you’re going to play, which one are you driving?

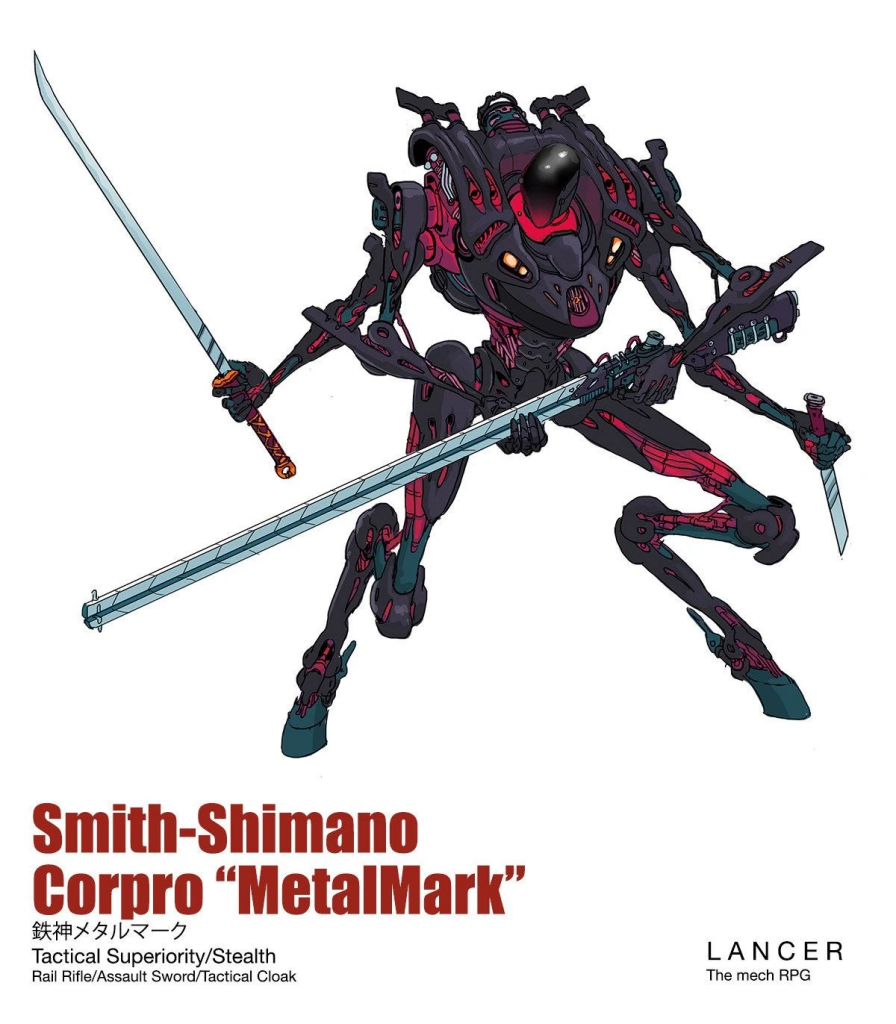

Kai: Left to my devices, I probably would default to a Metalmark. I really like that one from the SSC catalog because it is probably their most normal mech. It is just the straight up, it’s what’s referred to as a “line mech.” All of the manufacturers have one that’s kind of like the face of it. This is your default kind of troop. But it also has a lot of really great flavor baked into just some very simple and straightforward traits. It’s better at taking cover. It’s faster, it’s agile and it’s core power is wonderfully elegant in its simplicity. Turn it on and you are invisible. That’s it.

Miguel: I’m an Everest guy. That was one of my favorite ones to write the description for. And I don’t get a lot of time in my day job. Outside of scripted scenarios, I’ve never actually cracked license level two. So I’m familiar with the Everest. I like it. I’ve always loved the grunt mech in games and anime and the Everest fills that slot while also being just a solid, real decent all rounder. And I think for that reason, I like it the most.

Kai: There was also a really funny sort of “blink and you miss it” joke from the earlier versions of Lancer that didn’t fully make it into the current version built around the Metalmark. Which is in earlier versions of Lancer, pilots had to wear a hardsuit in order to use a mech. It was not an optional thing. It was considered a necessary piece of interface equipment. Couldn’t just get in the cockpit in a t-shirt and jeans. You had to be wearing a suit of armor. It was designed to protect you from neural feedback. And I guess probably just protect you, the pilot, because I imagine being in a mech fight is like being in an ongoing car crash.

But there’s this wonderful bit in the description of the Metalmark where it talks about all Metalmark models come standard with a Smith custom leather gimbled pilot seat to ensure comfort on long deployments. And so they’re selling you the Metalmark with this leather seat that if you’re wearing a hardsuit, you will never actually feel or notice. And to me, it’s just the perfect example of Smith Shimano design in practice. They do all these fucking extra over the top bits to really emphasize that you are piloting the luxury mech, and none of it really matters.

Miguel: Yeah. They’re the type of company to put a carbon fiber cup holder in your car, and you sit there and you’re like, that rules. And then you wonder for a second, you’re like, but why? Completely unnecessary.

Kai: There’s also the great flavor text in the shock knife part of the Metalmark license, where basically if you lose the shock knife in combat, you have to submit a written apology in order for them to give you a license to print another one. We’re in a setting with advanced 3D printing, super magic printers that can basically just replicate a thing on the molecular level. It shouldn’t matter, but they make you do this anyway. They make you go through this song and dance, this shame ritual because how could you use our weapon and lose it? You fucking rube.

Condit: Yeah. You have to have that artificial scarcity taken to the Nth degree.

Miguel: Yep.

Kai: Yeah. And there’s actually another SSC mech, the Monarch, which is the big missile platform. And they talk about how they enforce the scarcity on that one so strictly that each designer who works on the Monarch, their personal design only gets 10 printings ever. So one person makes a Monarch and it gets printed 10 times and that’s it. Then they have to bring in another designer to put their spin on it. And it even talks about how this mech is so good that the only thing that prevents it from achieving total battlefield dominance is this emphasis on purposeful scarcity. They are literally hamstringing themselves just to make a point that they are about the exclusivity and the luxury. They could dominate the battlefield, but that doesn’t give them clout.

Condit: I had missed that one, honestly.

Kai: Yeah. There’s all these great bits and pieces throughout the flavor text in the mechs and mechanically the Monarch is also good, the Metalmark is also good, but I do love how they’re all bookended with this great flavor text that really grounds everything in a world. And oftentimes grounds it in ways that ring true to actual military development. The IPS-N Raleigh is a great example of this because the flavor text talks about how the Raleigh is actually kind of a failed project. It was supposed to be the new figurehead mech for IPS-N, and then when they pushed it out, people didn’t bite. They didn’t like it so much. And so that to me is something that really sets the tone more than just every mech being the best of its kind and every one is a success and everybody loves it.

And it’s like, no, sometimes military development is weird and messy and full of stuff that didn’t go as planned. That was actually something that I worked a lot on in Battlegroup as well when I was writing the histories of all these different naval ships. In a lot of cases, the development was weird and it went places that it wasn’t intended to or it didn’t wow the military commanders who were looking at it. There’s a whole argument going on about whether battle carriers are useful or not. There’s a ship in there that is many, many centuries past its sell-by date, and the only thing that keeps it in service is the fact that there are so many of them, it’s more efficient to just keep pressing them into service rather than trying to retire them and replace them with something more expensive.

And I think to me that that’s always the very interesting part of a game with a military focus is looking at all the stuff that doesn’t work, that isn’t just shiny and sleek and works perfectly all the time. But you have this feeling of, well, yeah, it didn’t quite work out during trials, but then it found a niche audience and we keep using it because it’s cheaper than replacing it with the new stuff.

Miguel: Yeah. It’s funny that you brought up the military language. I remember writing this, I was doing a ton of research, so I was on a lot of Raytheon and Lockheed Martin sites and stuff like that.

Kai: Yes.

Miguel: And I’m just trying to find the language to the point where my Twitter ads were all Raytheon and Lockheed Martin.

Kai: No, no, no, no. My YouTube recommendations are a swamp. It is actually awful.

Miguel: I would get recommendations from missile defense systems pushed to me on my Twitter feed, just like, come check it out. Come take a look at it. And I was like, I respect that you think that I have that kind of a budget.

Kai: And those Raytheon commercials, those are fucking hilarious.

Miguel: They’re so grim and strange.

Kai: It’s like watching Robocop.

Miguel: Yeah, it’s like music set to very, it feels like you’re watching a promo video for a new HVAC system or something like that, but then there’s a rail gun that just shoots an old T55 and just annihilates it.

Kai: I was watching one, and I swear to God, they lifted sound effects from a Call of Duty game or something.

Miguel: Yeah.

Kai: They’re showing somebody using a console to control this artillery system, and it’s over-dubbed with all this stuff, and it’s like, you guys have got to be fucking kidding. And it’s just like, ah, it’s so awful. And yet it’s the bucket of poison I can’t stop dipping my head into, because there is something about it that I love so much.

There’s an old Manticore system that got cut from the game during playtesting. Just the system wasn’t very interesting, but I loved the flavor text that Miguel wrote for, because it’s got this wonderfully grim, dry dispassionate sort of dark humor. It talks about haywire ammunition, which carries a codec-slurry payload that upon impact, unleashes viral code to systems in close proximity. The effect is lost on soft targets as haywire codec-slurry ammunition is only chambered in 30mm and up. And I just love the way that’s phrased. The effect is lost on soft targets. Oh, well, why is that? Because it’s only 30mm and up. Yeah, I bet it’s lost on soft targets.

Miguel: Along with a lot of other part of soft targets too. I will say on the flavor text point, that was one of the original things that Tom and I, before I saw any systems, before we had systems mapped out what they would do, a lot of these early systems were just top down like, I’m going to write out flavor text based off of an evocative name and a one-line sentence that Tom had written in our original Google Doc of like, I want this system to do this. And then I would write up a sentence or two about what I imagined that would look like without knowing what the rules were. So a lot of that got refined out as we did development, but sometimes we have mechs and systems in here where flavor text does not explain, to use Kai’s example of the codec-slurry, not having an impact in soft targets because it’s chambered in 30mm and up.

It gives you a sense of the size of the weapon. That’s on one end of the spectrum. And then the other end of the spectrum, we have things like the Dusk Wing, right? Which the flavor text that describes the weapon systems and the sort of sensor systems that the mech has is just a debrief recounting the horror what these pilots experienced on a mission.

One of the things about Lancer, I find it hard to like the things that I write, but I really do on occasion like to return to Lancer to look at it and just get to sink into a rule book. It was something that I remember really loving when I used to play roleplaying games all the time and hoping that others do, and we’ve had it happen in this conversation as well. It’s a big-ass book and there’s a lot of stuff hidden in there just by virtue of its size that, I find it on the narrative side fun to return to for inspiration and to hopefully evoke that sense of the setting being very, very large and having room for tons of different stories.

Kai: Yeah. Lancer’s flavor text when it comes to mechs follows the kind of cadence that I’ve noticed where you will have stuff that is presented in this very sort of technical military ad-copy sense, and it will kind of keep going and it’ll keep going and it’ll kind of lull you into following that along and then it’ll hit you with something else. And I think that that’s more striking than just having everything be one or the other because you’ll be going along and you’ll be reading a long treatise on the first specifications for the SCYLLA-class NHP and where that comes from, and it’s all very technical. And then immediately across from that, you have the vorpal gun where all it says is “DO NOT STARE DIRECTLY INTO THE APERTURE.” And it explains nothing else.

And I think you need that blend. I think you need to have that sort of up and down cadence where it paints a picture of a world where there are these weird unexplained instances of things that you not even as the reader fully understand what is going on with this thing. But you put it on your mech, it’s a gun. You’re like, okay fuck it. I don’t need to know how this thing works. I know it does big dick damage. Here we go. Just don’t stare into the aperture. Fine, whatever.

Condit: And speaking of the unexplained and the bizarre there, I warned you about an hour ago I think now that I have a philosophy degree, so we do have to talk about NHPs for a minute here. From the context of thinking about the theory of mind and just what a non-human intelligence would look like, the NHPs are fascinating. The idea of shackling being a thing that you impose these kinds of rules of how to think on a foreign mind or an alien mind, and the end result is a now significantly less alien mind that says, “Oh yes, you totally should have done that to me.” But how are we supposed to know whether it was actually right?

So when you’re going into bringing NHPs into this game, first, why NHPs in general? And second, how did you land on this particular conception of them?

Miguel: You know, it was something that we realized setting in to write it, a lot of science fiction properties have AI and have artificial intelligence, or robot companions, things like that. And it was certainly something that we wanted to have in this setting and something that I wanted to write in. But I have to confess that I don’t have a very deep technical knowledge of it.

So what I wanted to do was sort of start at the end, which is, here’s what I want it to look like, and then branch out from there with a ton of possible explanations, sort of mirroring how they’re understood in setting, which is no one really understands what they are in setting. They have a ton of theories, they have a ton of ideas about what these things are. No one really knows how they work, but they know that they do work if they apply this process to them, right? And if they continue with these rituals to keep them in line, it will keep an NHP functioning as a person, or as what a human being would describe as a person.

So starting from there, I realized I didn’t want to have any one explanation for what they are, what they could be. It’s just to keep a sense of verisimilitude, keep a sense of truth to the setting right?

Because that was also very interesting for me as a writer to not know what they are. To have that as an open question that I wanted to continue to try and answer. Led me to write in a ton, or was very generative for me to write in a bunch of potential explanations. Which thinking of it as a game now, for players who want to play as or want to have campaigns that involve and explore the nature of being and ontology for NHPs, I wanted to have that be a thing because I was excited about the questions sort of on a more like, the slightly more mystic side of wanting questions in this game, as like a counterpoint to the ideological side, I guess the political material side of it.

Writing in mystery to the setting I felt like was something really important. Not having a technical explanation for it prompted me to try and find a “non-technical technical” explanation. Like one of the things that we talk about Lancer is that it’s a very soft science fiction setting with a hard sci-fi coat of paint, right? Wanting to explain what NHPs are had me write in like para-causality, which unlocked a whole different side of the setting that felt like a good thing to have in there to prompt questions for storytelling and further setting exploration.

The NHP stuff specifically was written a bit because it felt like it needed to be in there. Like I was saying earlier, science fiction settings commonly have things like AI. I didn’t want to do a Butlerian Jihad, there’s no AI here. But I wanted to have just another avenue for players and readers to explore the nature of being in a science fiction setting, I suppose is the most concise way I can say it. And also to sort of wrap them in inextricably with Union and their politics and the present moment of the setting. To make them another contradiction that players would need to, or could interact with if they wanted to in the setting.