SPOILER ALERT: This review contains significant spoilers for the Cursed City novel. But then again so does just playing the game.

To accompany the recent Cursed City board game release, Black Library published a tie-in novel of the same name. Despite the title it is not in fact a novelisation of the game – instead it’s a prequel, telling the story of events right before the game kicks off. “Prequel tie-in novel for a limited-run board game” isn’t a promising description for a book, even in the world of Games Workshop where this kind of marketing collateral has become a reasonably common part of the release strategy, but the good news here is that what’s on the page is better than that rather dismal premise.

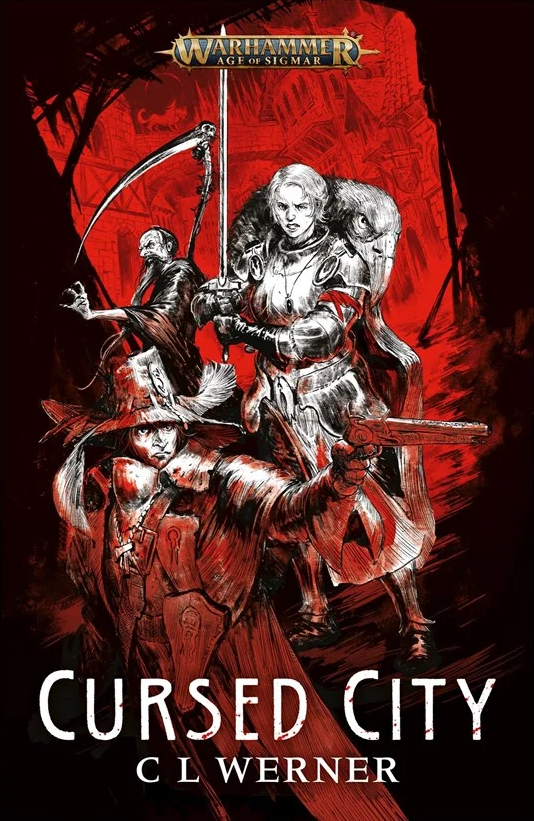

Somewhat confusingly, most of the characters here are not actually from the game. On the protagonists’ side we have three main characters, in the shape of Emelda Braskov, Gustaf Voss, and Morrvahl Olbrecht; you probably only recognise the first one of those names from the boxed set. She is the last living member of the noble families of Ulfenkarn, who were otherwise completely absorbed into the Thirsting Court, the vampiric aristocracy under Radukar the Wolf. Gustaf is a Sigmarite vampire hunter, who has come to Ulfenkarn to link up with Jelsen Darrock, while Morrvahl is a death wizard who opposes the Wolf from his own self-interest rather than any heroic ideas about “freeing the city.”

It’s a fairly motley crew – Emelda and Gustaf establish a decent relationship early on, but both are wary of Morrvahl, who sure claims to be on the side of right but can’t help being very creepy, what with his staff that latches on and eats people’s essence and the going around summoning magical nightmares. The three aren’t the most original characters in the world, but they’re distinctive on the page and you’ll rapidly come to enjoy their back and forth.

The first half of the book is divided between actual chapters and then a prologue and six interludes, which are short 1-2 page sections where a denizen of Ulfenkarn comes to a grisly end. These quickly become known to the wider citizenry as the Baron Grin murders, so-called because the murderer leaves the very emphatic calling card of flaying the skin from the faces of his victims. These brazen acts are initially investigated by the Volkshaufen, the human watchmen of the city, but as they escalate Radukar himself takes an interest and places himself in charge. The Wolf knows there’s something extra-suspicious about the deaths as the corpses are untouched by carrion, which is unusual for a city filled with ravenous bats and rats perfectly willing to attack living people, let alone dead ones. We spend a surprising amount of time with Radukar, who is less a distant final boss and more of an active participant in the narrative, and his is a great character – you get a real sense of the power and dread of this otherworldly, enormously strong vampire lord who has reduced a once-proud city to his own personal dictatorship. He exercises a kind of personal terror, combining an efficient administration with an army of undead skeletons and ogres (sorry, ogors) underpinned by his own immense strength; it’s a neat bit of development of the world that answers questions like “how does this ancient vampire lord actually run a city?” that often go unanswered in this kind of narrative.

The second half is mostly full chapters with just one interlude (in which the murder has some distinctive characteristics that suggest that it’s perhaps not all it seems), with the revelation that Baron Grin is not one person but a whole Khornate cult trying to summon Slaughn the Ravener, a Daemon Prince of Khrone, in the underground lair in which Radukar slew him many years ago – this act as saviour of the city being how he initially entrenched himself there.

In a lot of ways this feels like an old school Dragonlance novel, in the good ways that those were enjoyable hack’n’slash romps, but with a defter hand doing the writing. There’s a lot of incident, which is basically a requirement for a light fantasy novel which is meant to simulate the way the board game plays, but it’s underpinned by the surprisingly strong characters, and keeps things lively with the multiple different threads in play and the internal and external conflicts for each side; as mentioned above, Emelda and Gustaf do not trust Morrvahl for the obvious reason that he’s both superior and odd, and there’s an additional vector for internal strife with the introduction of Loew and his band of anti-Baron Grin vigilantes who can’t quite decide if the last of the Braskovs is someone they want around or not. Radukar, meanwhile, is more focused on hunting down the murderer than on dealing with our protagonists, at least in the early going before all threads are drawn together for our conclusion, while in the background the people of Ulfenkarn are just trying to survive, and the minor characters we meet give us lots of little insights into what the city and its citizens are like.

That’s all well and good, then, but what about the problems? The key one is likely to be obvious – this is a prequel and so the conclusion ends up being pretty unsatisfying. There’s a titanic final battle with Radukar in which he doesn’t win but also doesn’t lose, Gustaf (a non-game character) is summarily dispensed with, and Emelda sort-of escapes but not really, for some reason ending up imprisoned rather than outright murdered for reasons that don’t really make sense except that the opening scenario for the game has the characters breaking out of gaol.

The other really strange thing is just how little this actually serves as a prequel to the events of Cursed City, the game. Here’s the description of the opening from the board game, under “Chosen by Fate” in the Quest Book:

Captured by agents of the Wolf, the heroes found themselves interred in the dank dungeons of the Ebon Citadel… Only the outcast aelf Qulathis managed to evade capture…. the heroes fled to the relative safety of the Adamant, the sleek airship of Kharadron Trade-Commodore Dagnai Holdenstock.

Literally none of this is in this novel. We don’t even meet 6/8 of the heroes. Emelda is a protagonist, while Jelsen Darrock is mentioned and appears in the concluding scene; Brutogg is described but not named, and that is pretty much it. Bizarrely, Morrvahl also disappears – he leaves the final battle unconscious but alive, and is in the cells with Emelda, but then he simply does not appear in the game and instead a different death wizard – Octren Glimscry – takes his place. It’s hard to know quite what’s going on here; was Werner working from an earlier draft which got significant revisions after he’d already filed the manuscript? It makes a kind of sense to keep the prequel focused mostly on the events before the game and not have a lot of the adventure take place ‘off-screen’ in a tie-in novel, but not to mention the majority of the characters at all is kind of weird. Even just a few scattered references to these other characters would have gone a long way to tying the two things together; instead we spend more time learning about a Khorne cult which has been utterly destroyed by the time the board game actually happens.

With all that in mind, then, what is the actual function of this book, and should you bother reading it? It’s hard to definitively say yes – I don’t feel like I wasted my time with it, but then I was reading it for the express purpose of review. I also own a copy of the game so can actually move on to the next part of the story, which puts me in somewhat rarefied company, with the product now out of print and a lack of clarity over whether it will return or not. If you’re taking this on its own, and you’re interested in some fun, pacey Age of Sigmar action and don’t mind too much if the conclusion is a bit open-ended, then it’s perfectly fine on those merits. If you were looking for either “a complete, standalone experience” or “the opening act in a well-planned trilogy which all links together,” however, it kind of fails on both grounds, and I’m certainly glad to have the ebook version rather than the pricier collector’s version.