This review contains minor spoilers for Bloodlines.

Way back in 2018, Games Workshop announced a new imprint for Black Library – Warhammer Horror. The idea here was fairly simple – take the existing Warhammer universes and the horror elements that were already present, and tell stories that focused on that aspect. With a slew of novels, novellas, and short story collections following on from the announcement, and more in the works, this was apparently a successful move, and so enter Warhammer Crime. Where Horror takes aim at the terrifying and supernatural aspects of the setting, Crime sets its sights on the seedy underbelly of the Imperium – hive gangs, criminal cartels, the corrupt and the compromised, and of course those Imperial institutions desperately trying to oppose them.

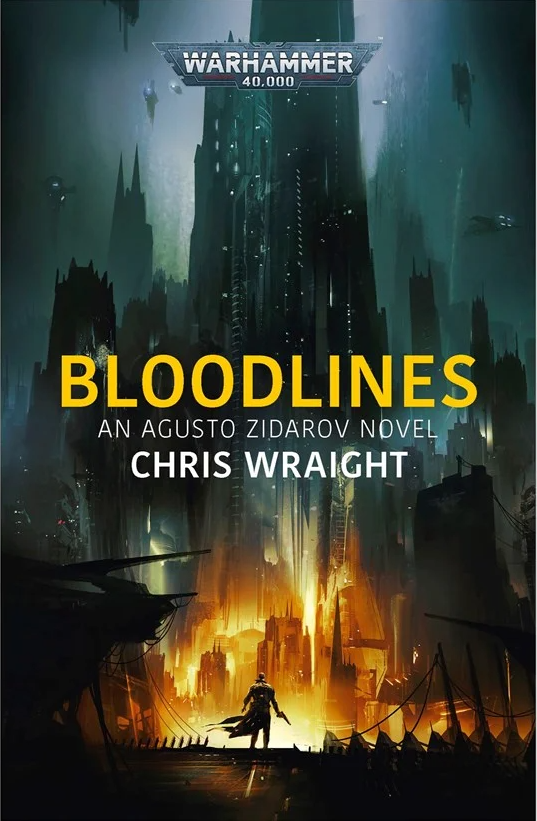

The first entry into this new series is Bloodlines, by Chris Wraight – already a prolific author for BL, and someone who, although I had not previously read his work personally, came highly recommended by friends. Before we begin, a quick thank you to Games Workshop for the kind provision of a review copy.

Bloodlines takes place on the world of Alecto, which sits somewhere between a civilized world and a Necromunda-style hive world – the story happens largely in the immense and oppressive city of Varangantua, but there are still seas on this world and beaches which are apparently still clean enough for the wealthy (known in Varangantua as the ‘gilded’) to bother visiting them.

Said gilded provide the thrust of the narrative. This is not a novel about the clashes of underhive scum and street-level violence. The foot soldiers do make an appearance from time to time, but this is a book primarily concerned with the machinations of the incredibly wealthy – both the outright criminal cartels and the great corporate concerns that mix their legal businesses with a variety of less-legal pursuits. The two worlds are not so much linked as freely intermixed, and both taint the operations of the Bastion, the all-encompassing force that passes for law and order in Varangantua.

Into this morass is thrust Agusto Zidarov, a probator (read – detective) with the Bastion. Zidarov is an unlikely figure for a Warhammer novel; though he’s done his time in the sanctioners (the street-level cops who do the breaking heads and busting down doors that passes for day-to-day police work on Alecto), by the time we meet him he’s middle-aged, running to fat, and mostly concerned with trying to keep his teenage daughter from signing up to join the Astra Militarum. He has a weakness for paraja, a staple food mostly consisting of fried meat and greasy bread. There’s a few key action scenes, including one incredibly reckless and viscerally-described car chase, but mostly the intensity is low and the energy is more Poirot than bolter porn.

Plot-wise, we have two narratives ongoing – which are linked, but not in the way that seems obvious to begin with. The first is a request from Udmil Terashova, one of the gilded and joint head of the Terashova Combine, one of the enormous mostly-legal conglomerates, for the Bastion to find her missing son Adeard. Zidarov immediately smells a rat, premised mostly on the fact that if someone as rich and powerful as Udmil really wanted to find someone she thought was missing, she could afford much better than a single probator to do it quicker and more discreetly. Second, we have the practice of cell-draining, introduced obliquely in the prologue and quickly uncovered by Zidarov in the early going. Those familiar with the 40k setting will be well aware that among the long-lived xenos races, the functionally-immortal post-humans of the Adeptus Astartes and Adeptus Custodes, and the mechanically-enlivened Adeptus Mechanicus, there are also ordinary humans who keep on trucking thanks to the magic of rejuvenat treatments. In theory these are provided by legal means, via lab-grown stem cells and other biological materials, but at least in Varangantua there’s also the illegal version – cell-draining, whereby the young and the healthy are abducted and forced into coffin-like boxes which slowly bleed them dry. The practice is despised by the Bastion, and was previously stamped out, but now it seems to have crept back in.

In theory, Zidarov can call on the enormous resources of the Bastion in his investigation, but in practice the enforcers are stretched too thin, and are too compromised by their funding stream – the wealth of the very same cartels and conglomerates they’re meant to be policing – to be reliable. An early failed bust wrecks Zidarov’s credibility with his superior, Castellan Vongella, and leaves him swimming against the tide for much of the novel even as he works to solve a case that she assigned him in the first place.

The characters on display here are a real highlight. We spend all but the prologue with Zidarov, and as a consequence get to know him best, but the supporting cast is well-drawn and evocative – whether it’s the aforementioned Castellan Vongella, a chief of police torn between the weight and responsibility of her office with the very real knowledge that its ability to operate is predicated entirely on keeping wealthy benefactors on-side, or Gyorgyu Brecht, Zidarov’s friend and long-time colleague who is not necessarily bad at what he does but prefers keeping his head down and focusing on what he can control, or Alessinaxa ‘Naxi’ Zidarov, Agusto’s daughter whose genuine faith in the Emperor is driving her to join up for the Guard – or possibly something more insidious, as hinted at in the sub-plot which goes nowhere in this book but is very obviously setting up a hook for a sequel.

The setting, too, is filled with excellent details. The focus here is very much on ‘civilian 40k’ and zooming in to a level of detail which can be obscured in stories about fleet battles and grand-army clashes between elite supersoldiers, and Wraight handles it excellently. This is definitely an Imperial world, with the institutions you would expect to find there, and it’s connected to the wider Imperium – a significant part of the plot is concerned with the operation of surface-to-orbit trade – but not that connected. Alectans don’t know anything about the Cicatrix Maledictum or the Dark Imperium; people involved in off-world trade know that there’s something going on in the shipping lanes but they don’t really know what. They’ve heard of xenos, but they’re not sure if they’re real or mythological, and all they know about the Imperial Guard is that people sign up and then mostly they don’t come back again. There’s servitors and servo-skulls and Ecclesiarchy propaganda and so on, but not a Space Marine or boltgun in sight. Life is hard, but there’s gradations of ‘hard’ – from the grade-eight habs at the bottom of the food chain to the grade-ones for political workers and high functionaries, never mind the mansions and gated districts of the gilded. The gilded themselves are a world apart, both in physical space and also in the way they live – at one point Zidarov observes that it’s not so much that they don’t care about the lower classes, so much as that the actuality of the hab-eights’ existence can’t even penetrate their reality.

It all makes for a novel which simultaneously is steeped in 40k as a setting but also could, easily, be taken out of that setting and function perfectly well on its own merit – the specific details are all Warhammer, but they don’t have to be, and it would fit neatly into any far-future dystopian setting. If this sounds like a criticism, it isn’t – I would far rather read a genuinely good novel that happens to take place in a setting I love than a mediocre one which gets cheap heat by name-dropping as many familiar elements as possible.

If I had to criticise a few elements, I would say that the first 100 pages or so are a little slow going, and that the sequel hook mentioned above is included by way of taking up just enough page count that it’s annoying to get zero resolution here. It also cheats at building tension a little bit by way of the protagonist simply neglecting to think about the details of a clandestine meeting for a hundred or so pages.

Those minor critiques aside, though, this is a great book, and a promising first entry for the new imprint. If you’re at all interested in the premise of Warhammer Crime – or you just like reading well-written fiction set in the Warhammer 40,000 universe – then I would recommend checking it out.