Author’s note: Given the scope of the piece and what it specifically examines, this article was written solely about the base Bioshock: Infinite game, without playing or considering the Burial at Sea story expansions as they were not part of the original work.

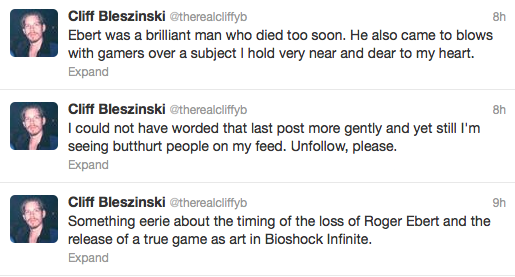

It’s been a little over seven years since Bioshock: Infinite was released to wild fanfare and massive acclaim. Given how long it has been, it’s probably worth recounting a bit how wild and massive it was — the reaction that jumps most keenly to people’s minds even now, probably, is developer Cliff “cliffyb” Bleszinski’s hilariously embarrassing invocation of Roger Ebert’s recent passing on his way to ordain the 2K Studios first person shooter/exploration hybrid as a “true game as art:”

He was very far from alone in those comments, however. Game Informer gave it a perfect score, the vast majority of other publications lined up to give it something in the 90-95 range, and even those reviewers who had problems with some of its gameplay foibles lauded the story for making them think. Player reaction was if anything more effusive — cliffyb up there is speaking as a fan, after all, and though there’s plenty to shake one’s head at in regards to using the game’s release to continue grinding his axe against a dead man, his praise for the game itself is if anything restrained. At the time, this was all a bit much, but some of it was perhaps warranted. Yes, there had been games with intentionally-told, thematically-considered stories before — the preceding two Bioshock games were precisely that — but neither of those games really grandstanded with the sort of expensive pop culture song licensing and loose, expansive pop-science riffing that Infinite put on offer.

Also unlike the previous two games in the series, it married the themes and the theory to a story that offered a tangible, personal connection to hold onto, one that was perhaps machined for the 18-35 male demographic that the game was aimed at: an emotional thrill ride alongside Elizabeth, a barely-nineteen-year-old Disney princess who both does and does not need saving in turn, full of quirky life and strange magical powers, with the player put in the role of a broken, self-pitying alcoholic who is good for nothing (except being a ruggedly handsome older man who plays the acoustic guitar fantastically well and can kill an entire standing army with a Mauser pistol and a couple magazines of ammunition) and swings wildly between seeing her as a burden and as salvation. Helps that he turns out to secretly be one of the most important people in the world, too.

I came back to this game for two wildly divergent and mostly unrelated reasons; first, and more prosaically, we sit in the wake of yet another masterfully-reviewed, Game Informer 10 of 10 AAA game release in Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us 2. To indulge in understatement, TLOU 2 has had a quite different reception than Bioshock: Infinite did. The user review score on Metacritic sat down around 3.2 for much of its first week of release. This was mostly due to right-wing brigading and trolling from cultural reactionaries who hadn’t played the game and had no plan to, but on the other side of that coin, marginalized people looked at how the game meted out misery and violence to characters like them in its world — with a trans male of color becoming a particular focal point for this — and questioned what themes and messages the game was really trying to convey. It’s worth looking back and seeing if Bioshock: Infinite actually executed better than TLOU 2 did…or if there’s some other explanation for why it didn’t start getting the “hey, wait a minute…” treatment until after the initial hype had died down.

Second, George Floyd was killed by the police in Minneapolis on May 25th, and the shockwaves sent across America’s precarious cultural and political fault lines since then, with the resurgence and mainstreaming of the Black Lives Matter movement worldwide, constitute a watershed moment. In this moment, openly talking about white supremacy is not just possible but encouraged…and therefore it’s interesting to go back to 2012 and early 2013, when Bioshock: Infinite was made and released, to re-examine how it dealt with that thorny issue, then and now.

We’ll deal with the second question first, just because white supremacy — and specifically settler-colonial white supremacy, with its glorification of the conquering, subjugation, genocide and replacement of indigenous people — is such a big part of the Bioshock: Infinite package. The game takes place in the floating city of Columbia, a sort of mirror-image of the underwater “paradise” of Rapture from the first game, and the city itself as you see it in the game’s opening is probably the most incisive critique of white supremacy present in the work.

Columbia is a nowhere land, created entirely out of American mythmaking to cover the nation’s bloody past; it’s 1912 in the story’s timeline, but the city itself exists outside of the material and technological shackles of that year just as it has escaped its physical ones; licensed popular music like “God Only Knows” by the Beach Boys and “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” by Cyndi Lauper exist in barbershop quartet and calliope machine arrangements alongside contemporary songs like “Let the Circle Be Unbroken” and “After You’ve Gone,” and both alongside popular religious music like “Agnus Dei” and, in the sound design’s most prominent instance of going back to the same obvious well one too many times, Lady Comstock’s theme, “Lacrimosa.” The fashion is period appropriate save for perhaps too many respectable men going out and about without hats on, but the architecture is as much of a mishmash as the city itself, careening from colonial brick to newer turn-of-the-century high-density neighborhoods later in the game, with huge faux-Greek and Roman statuary dotting both the skyline and the city’s many winding streets. Perhaps the most striking aesthetic parallel to our current time occurs quite early, just as Booker is recovering from the first of many baptisms in the game. (An aside: the game plays fast and loose with whether it’s using the baptism metaphor to make or ironically undercut its point, but one of the main effects is to make Columbia’s religion directly evoke a Great Awakening-era Evangelical Christianity without ever doing anything like including the cross in Columbia’s iconography and pissing off the then-more powerful religious right.) He comes up for air and sees these three utterly ludicrous statues of the Founders, the three historical founding fathers of America that Columbia and its mad prophet leader, Zachary Comstock, claim for their own:

That’s buff Benjamin Franklin there on the left, yes. I remember finding it amusing and over-the-top at the time; given how right-wing political cartoonists now draw Donald Trump in their screeds, however, I now just find it amusing. I recall younger me having some thought along the lines of, “Wow, Comstock’s really got them brainwashed if they actually believe Franklin was that yoked.” Now, of course, it’s clear that this is fully in-line with the rest of the city: the fascist “nostalgia” that creates and reifies the perfect past out of nearly whole and certainly bloody cloth is made physically manifest in the city of Columbia. The city is a more elegant example of the philosophy of those guys you see out there waving the Confederate and American flags side-by-side at counter-protests against Black Lives Matter: Far from being confused, they understand on some level that for the American white supremacist, those two flags represent the same thing. There is an unbroken line of violence from the brutal Indian wars as the settlers pushed inland up and down the east coast to the chattel slavery of the Confederacy back to the lynchings of the Klan and Jim Crow and continuing up to this very day. Columbia represents all that violence, rolled up into one package. This culminates in the game’s most brutal and effective setpiece, where the genteel, polite, and fun-but-somewhat-off fair that Booker attends at the end of the game’s tutorial and introduction turns suddenly into the lynching of a white man and Black woman for miscegenation, with Booker being selected to begin the stoning himself.

Then six hours into the game, they fuck it all up. There are warning signs, of course: the very few Black characters who exist in the game, even incidentally, are written rather broadly and (with one blink-and-you’ll-miss-it partial exception involving a janitor) never codeswitch. There’s an attempt to shoehorn the Irish in as being subjected to the same abuses as the Black slaves that I hadn’t noticed before, referencing one of the more pernicious myths put forward by pro-Confederate historians and Lost Causers. All in all too much time is spent wallowing in the viciousness of the Columbian ideology and revisionist history and not enough time effectively rebutting it…but then, of course, the game has no interest in directly rebutting it. The game intends to counterpoint it, which is something very different indeed.

When Bioshock: Infinite goes off the rails, it goes off the rails hard, and it primarily does so because despite what the first six hours or so of the game might signal, it has no actual interest in interrogating settler-colonial white supremacy or using it as anything but a backdrop. As soon as Elizabeth begins opening portals to different versions of the city and the quantum physics and multiverse theory stuff goes from being fodder for strange chatty asides by the Luteces to the meat of the plot, the game stops using Booker and Elizabeth’s adventure to examine the city of Columbia and starts using the city of Columbia to examine Booker and Elizabeth’s adventure.

Players get to see how this is going to go immediately in the mystifyingly silly Chen Lin quest line. Summarized, here’s what happens: Daisy Fitzroy, head of the left-wing uprising in Columbia calling itself the Vox Populi, makes a deal with Booker to trade an airship for a cache of weapons owed to her by the gunmaker Chen Lin. Booker and Elizabeth go to find Chen Lin, only to discover him dead in a cell. But wait! The Luteces appear and explain they can just jump to an alternate timeline where Chen Lin isn’t dead. Booker and Elizabeth do this, but in this new timeline, Chen Lin’s tools have been stolen. So Booker and Elizabeth go to get these tools, which they’ve seen before and know are machine presses that take up entire rooms, and then only realize once they arrive that they can’t move the tools. Here Booker drops a line — “we really should have thought this through” — which is absolute poison; having a character diegetically recognize how stupid the situation he’s put himself in doesn’t make the situation better. But it’s fine, because Elizabeth can just jump to a timeline where the guns already exist! Booker and Elizabeth do this, and satisfied that they’ve held up their end of the bargain with Daisy, go to collect their airship.

The problems here are obvious. Despite Elizabeth doing all but looking directly into the camera and explaining the concept of alternate realities to you slowly in small words over the course of the quest, the two are shocked to find that this Daisy Fitzroy has no idea who they are, having never made any deal with Booker for guns, and what’s more, she clearly doesn’t need the guns they claim to be delivering, because the guns were already in her revolutionaries’ possession in this universe that Elizabeth moved them to. This is roughly akin to making a cheeseburger and fries in your own kitchen, pouring yourself a beer, sitting down to eat, and having someone barge in and demand you pay them for delivering you a meal. This absurdity is quickly pushed aside, however, as the plot gadflies off to the next plot point, which is that the Booker of “this world” is dead, having sacrificed himself a couple days back to kickstart the revolution. Negotiations with the Vox Populi fall apart in short order, and suddenly the enemies are now the guys wearing red instead of the guys wearing blue.

The idea that the Vox Populi and the Columbians are fundamentally the same in everything but aesthetics is key to the back half of this game, and manifests in the rebels committing ever-increasingly gruesome war crimes — lining up civilians and shooting them, torturing women, letting you know in only slightly-veiled terms what they’re going to do to Elizabeth after they kill you, and in two rather egregiously ham-fisted moments, aping the Khmer Rouge by ordering the killing of anyone wearing glasses, and brutally scalping a half-dozen of the administrators of Finkton. All the while, Elizabeth tells you more and more directly that both sides are in fact the same. Usually this is read as a facile, direct equation of radical leftism to settler colonialism, and it most certainly is, but it’s important to realize that ever since Booker and Elizabeth made that first jump to find Chen Lin, the game has ceased being “about” white supremacy. It is fully about these two characters and the concept of destiny, fate, and being able to change one’s future. Both sides have to be the same because the game has to reinforce that no matter how much you struggle against destiny (or whatever you wish to call it), outcomes have been preordained. This is actually an ongoing mechanical gag too — every time Booker is given a choice of doing something by pressing the left or right trigger, it’s either completely meaningless (like the “choice” below) or a third thing happens before he can do the thing he originally intended to do.

Here we circle back to our first question, and ask: Would Bioshock: Infinite have been less warmly received if it foregrounded the rather facile meditation on choice and relationship melodrama in favor of pushing the searing aesthetics and vicious indictments of “good old days” America into the background for the first six hours? It’s hard to say. On the one hand, it would have lacked the “we’re here making statements about society” signifiers that made the original Bioshock such a brainworm (the original game also notably falls off hard in its second half). On the other hand, the game fundamentally is the relationships between Elizabeth, Booker, Comstock, Lady Comstock, and even the Luteces, whose tedious quipping is probably the most poorly-aged part of the whole script. Frankly, I think the pacing is perfect for a game that has a lot of style but very little of substance to say, and whose main point of sale is a 19-year-old Belle knockoff losing her religion, in both meanings of that phrase, before your eyes.

More importantly, I think The Last of Us 2 and any game with its sort of “telling important truths” marketing push probably would get a lot more benefit of the doubt if not for Bioshock: Infinite turning out to be such an empty meal. The newer title certainly plays better — going back to Bioshock: Infinite in 2020 is a slog from a gameplay perspective; the various superpowers feel bolted-on and completely orthogonal to the plot and the world (why are brutal, purity-obsessed eugenicists so cool with bio-hacking themselves into hideous fire elementals or crow monsters, anyway?) and the guns feel anemic and rote. There’s a rather disorienting and difficult to explain skyhook conceit that allows you to swing around the arenas which by the end of the game greatly constrains the game’s encounter design (in addition to making every area feel like some sort of theme park), because every setpiece fight has to have them, one way or another, and the game’s final fight suddenly turns into a point defense mission the likes of which hasn’t appeared previously. Since the game needs its players to love Elizabeth — the entire thing doesn’t work if you as Booker don’t have a positive emotional attachment to the character — she’s both invincible in combat and constantly feeding you ammo and health, which can sometimes turn fights on higher difficulties or later in the game into exercises of “do you roll well on Elizabeth’s hidden loot chart to get the resources you need to win, or do you restart at last checkpoint?” TLOU 2 is far more cerebral and responsive, and just has better visual language up until someone gets a screwdriver through the eye.

Ken Levine gave an interview recently with Mark Cerny of Sony where he said some rather amusing but instructive things about his creative process; excerpting liberally (the full interview is available at the link):

“You don’t come up with amazing things that nobody has ever said before by being completely normal,” he continued. “You do it by being a little bit off, a little bit strange…. It makes me strange, because I have to go to strange places.”

“Sometimes you have to push past [the edge of reason] and make something outrageous and ridiculous, and then pull it back. But if you don’t go to the outrageous and ridiculous, you don’t know where that boundary is… You’ve got to go past it, and you’ll tell people things and they’re gonna look at you like you’re insane. And then you bring it back to something you can actually accomplish.”

Some people, myself among them, have poked fun at this for perhaps sounding a little bit like a deeply normal man attempting to cast himself as the Joker, but there’s something telling in that second bit. Bioshock: Infinite is a game that aspires to have something important to say, even if it’s not particularly concerned with what it’s saying that thing about. But in the end, Levine and his studio took a look at the edge and stepped back from it into the world of commercial success, crafting a visually sharp, slick rollercoaster ride with a Disney princess companion who endeavors to leave the player thinking, “wow, that wasn’t just another job for her, she actually really liked me” as the credits roll. In that sense, Levine created an excellent piece of art. The same way the Marvel Cinematic Universe does.

Final Verdict

Bioshock: Infinite was released on March 26th, 2013; when I went to my Steam library to reinstall it, it said the last time I’d touched it was April 10th, 2013. That sounds about right. It’s worth playing once if you haven’t played it before, but it’s far more interesting as an artifact of gaming history than it is as a full experience in 2020; there’s not a hidden gem there waiting to be rediscovered after the reception of the game cooled off. It retails for $29.99 now, which is “fine,” but if you wait you should be able to grab it on sale.