In the beginning, there was the End Times, and nothing was ever going to be the same. This is the time of turmoil. This is the era of war. This is the Age of Sigmar.

When you ask someone about Age of Sigmar you’ll field a number of responses, from those who only know the game in passing to those excited to talk about the current meta and everything in between. In its nine years of existence, beginning in the summer of 2015, Age of Sigmar has garnered a well-deserved reputation of being a deeply exploratory and innovative wargame, whose rules its ‘big brother’ Warhammer 40k now uses as part of its tenth edition scaffolding. AoS is, in fact, the second most popular miniatures wargame on the market and its presence in the market continues to grow. It still has its share of harsh critics; ever since before its shaky launch, this game has faced opposition from those who live in boardrooms and message boards alike. As we near the end of Age of Sigmar’s third edition, I feel it’s time to look back to that nascent period of strife for the game, and help better codify its history. The first edition of AoS was a time of upheaval, and there’s a lot to cover within the span of its three years, so let’s look back, so we might look forward.

As a bit of background, I’ve been playing Warhammer in some capacity since 2010, with plenty of Warhammer Fantasy Battles and 40k experience to draw from; I even played Nighthaunt as soon as Age of Sigmar launched, using their scant few holdover units from Vampire Counts without any knowledge they’d be a launch range in second edition. I hold no ill will towards any Games Workshop game, and I wouldn’t be working in tabletop design without this hobby. I say this because it’s almost impossible to talk about AoS without mentioning ones’ background, because for many, that very background is what drives disapproval with the game. The legacy of Age of Sigmar’s precarious launch in the face of corporate disaster coupled with the new life injected into the Old World by way of Total War: Warhammer has led to widespread apathy or resentment from many players who prefer Fantasy, but it was not AoS that killed that game. In order to understand why Warhammer: Age of Sigmar became Games Workshop’s core fantasy IP, we need to go back, to even before the first Stormcast was forged.

The End Times, in a Literal Sense

We’ll begin our story in September 2014, just about a year before AoS is destined to launch, with the advent of End Times: Nagash. The End Times was a portent of things to come with Games Workshop’s fantasy IP, and while it contained a number of large-scale releases for WFB, its name spelled out the situation – the game was ending. Warhammer Fantasy was not a game that sold well for the final three or so years of its lifespan, given the high unit counts and oblique ruleset and was constantly compared to Warhammer 40k, which consistently made up a far larger share of sales between the brands.

Alan Merrett, the then-Head of Intellectual Property at Games Workshop, echoes this sentiment. He cites the end of Warhammer Fantasy being based in the brand’s dwindled momentum, and stiflingly low rate of monetary return; their choice was down to restarting their fantasy IP, or becoming a Warhammer 40k company. The reception from both their store owners and players was similar, with months containing 40k releases consistently meeting or exceeding target numbers, whereas Fantasy sat on the shelves; even a strategy to pair smaller releases from both games resulted Wood Elves dragging down the sales of similarly-timed Eldar.

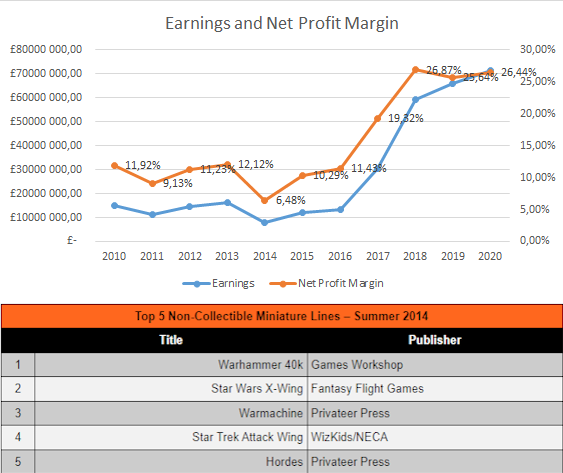

2014 also marked the second in five years that Warhammer Fantasy missed the top 5 for non-collectible miniature lines, where it never had achieved second place; this data was recorded by ICV2, a tabletop industry publication focused squarely on the business side of things. The comparison to 40k, which has held firm to the top slot in its category for nearly two decades, could not have been more discouraging. As a spoiler for later on, Age of Sigmar has held a Top 5 slot within these same industry metrics every year since 2018, with the odd exception of 2023.

The problem with selling fantasy at this time was not purely one of IP stagnation as Games Workshop believed itself to be a model company first and foremost. There was neither time nor money to resuscitate Warhammer Fantasy Battles as a game, with the priorities of its game rules coming after the production and sale of the kits themselves. This was said time and time again by then-CEO Tom Kirby, and reinforced a business model that failed to cultivate the large gaming communities we see today. It only makes sense that the solution was thought to be more “exciting” models, spurring the move towards The End Times, a last-ditch effort to right the ship, through the creation of the game’s largest ever models at the time.

Between Nagash in September, The Glottkin in December, and Thanquol the following January, these were centerpieces unlike any the game had seen before, something we now think of as central to Age of Sigmar’s identity. That said, this simply would not save Fantasy: In their annual report from 2014, Games Workshop recorded a year-over-year profit drop of £21.3 million to £12.3 million, ending with the resignation of their CEO, and a near-total turnover of the board of executives. In the cauldron of this corporate tumult, a vast overspending on Fantasy & specialist games, and a period where they were a mere “four to six weeks” from having to shutter their home office, Age of Sigmar was born.

The Launch Era: July 4th, 2015 – July 21st, 2016

It is not hyperbole to say that Age of Sigmar’s launch was perhaps the single worst-handled moment in the history of tabletop gaming. On July 4th, 2015, the core rulebook & Starter Set for Age of Sigmar was released, containing the very first Stormcast Eternals in a conflict against the Blades of Khorne. Notably, these Khorne releases bore a striking resemblance to the recent Khorne release in March of that year, especially the Skullreapers/Wrathmongers & Skarr Bloodwrath. It has been said, not confirmed, that the rules were authored over an incredibly short span, a trend we’ll see with the early written materials associated with AoS. It was meant as a fast-turnaround profit point, to show that the company could rebound, and revitalize a side of the company that wasn’t just Warhammer 40k.

Notably, a plethora of digital rules for the units not included in the new releases was also released on the 4th in Warscroll Compendiums, a first for the company. Digitally published rules meant that there was no hang-time for printing, assisting in the rapidity at which AoS deployed. The initial reactions, however, were harsh: There were immediate outcries of the Stormcast ostensibly being ‘Sigmarines’, and that the tonal whiplash of WFB’s more grounded setting to the high fantasy Mortal Realms was too much to bear. The transition to round bases, and smooth armor plating for the premier faction echoed heavily of 40k, but Yet the most scathing critique came down to the rules themselves, which inserted a number of thematic, silly rules into the gameplay, and entirely removed points. You were expected at this time to self-regulate between each player, and wound-counting became the de facto initial play method for balancing armies, which didn’t exactly work out.

On July 6th, many of these were compiled and made well-known through an Escapist article, further cementing Age of Sigmar’s unserious nature in the public eye. Contrary to outside eyes, no faction had more than a few of these ‘roleplay’ rules strewn throughout their Compendiums, but the fact that they existed (and were consistently repeated & reported-on) only magnified the ire surrounding AoS’s launch. Following this, several players physically destroyed their Warhammer Fantasy armies, with one Dark Elf player recording a literal funeral pyre for the game he felt he’d lost, which was subsequently included in further articles. I want to be very clear about this event, as well as with the roleplay rules — the vitriolic reaction associated with these events being publicized led directly to some of the blind resentment that still lingers over the game, but that doesn’t make it at all representative of everyone’s experience. In the opinion of the author, burning away hundreds of dollars worth of miniatures to prove a point isn’t something a well-adjusted adult generally does, nor should it be the single story retold about Age of Sigmar’s ill-fated beginnings.

Compounding on the above issues, at this time, Age of Sigmar was being reported by more mainstream ‘nerd’ sites, not just wargaming publications. One noteworthy example is the previously-mentioned Escapist; many general gaming publications sought to give the new system a chance, on the potential of it being as popular as 40k, which meant the flaws that existed in the launch rules were highly circulated, to the detriment of AoS. Some of the first things a less-enfranchised player might have seen about AoS centered on its core issues and not the promise it had.

Counterintuitively, from a game design perspective, the structure of Age of Sigmar’s rules received relatively positive reviews, and despite the rancor surrounding its silliness, many went out of their way to praise this scaffolding of a system. It is no surprise the phases, spellcasting, and cadence of Age of Sigmar have remained a constant throughout its editions, and the simplified, free warscrolls were a welcome means of reducing initial complexity for new players. This poorly-received launch, amidst the genuine promise of its rules, would eventually lead to the creation of many community-led endeavors, such as Warscroll Builder, a direct result of the game’s paradoxical reception. That said, yet another burden it bore during launch was felt most in its first six months, as much of its identity remained painfully tied to the World-That-Was. New factions like the Stormcast Eternals, Sylvaneth, and Khorne Bloodbound sat alongside Orcs & Goblins, Ogre Kingdoms, and The Empire – and would remain so until 2016.

The Launch’s Lore, or Lack Thereof

For the rest of 2015, Age of Sigmar essentially lacked coherent lore. There were initial pictures of some of the realms, as well as the outlining of the many Ages of the game’s history, but one common critique was that of its disjointed, distant nature; the realms seemed at face value to be abstract concepts with frankly silly location names, and the accompanying art did it little justice. The books which opened the setting, The Realmgate Wars, were met with derision from fans of Black Library, and speaking from experience…they don’t exactly hold up. A common critique of AoS that has clung to its reputation since inception has been this lack of cogent lore, and it started here. Yet there were glimpses, points of light amidst the smog of red and gold, of its potential.

To put a positive spin on it, we did know that the current era within the game’s lore was one of redemption & reclamation, taking back a world from the grip of Chaos, and in stark contrast to 40k, there was genuine hope that such a task was actually possible. These themes, of endless, righteous sacrifice in strange, unfamiliar high fantasy worlds would become the building blocks for the currently-fantastic stories told in the Mortal Realms, but to say it had a rocky start would be an understatement. Still, 2015 came to a close with the release of Archaeon and his Everchosen, a poignant reminder that The End Times had ended before many of its key figures actually received their breathtaking models.

While January as a whole would be extremely eventful for Age of Sigmar, being the release of another non-launch faction later on, January 2nd marked the beginning of a new trend towards accessibility for the company as a whole: Start Collecting!. These boxes launched at a cool $85.00 in 2015 (About ~$110.00 today) and made an immediate splash as the best bundles provided to armies not featured as a launch faction for a game’s new edition. Each of these came packaged with a centerpiece model, hero, and usually 1-2 troop options, but crucially they were often just a hair more expensive than some of the models contained within. The Seraphon Start Collecting! is perhaps the best-known example, with the Oldblood on Carnosaur kit retailing for the roughly same price as the combined box, meaning every other unit inside was free, or nearly so.

That’s not to say there weren’t wrinkles to this launch, though: “Malignant” was a race, not a faction, and the Mortis Engine was actually categorized as a “Deathmages” unit, meaning it needed to be allied into the surrounding Nighthaunt. This mattered very little at this point in time, as ally rules played fast & loose, but even with the release of the Grand Alliance books in less than a month, this quickly became a box with questionable legality. This was the first step in an aggressive push towards marketing Age of Sigmar as a more accessible game to 40k, given the game as a whole was smaller in scale for both models-on-the-table, and in its price point.

That monetary cost has fluctuated throughout its lifespan, but personally this period is when I started playing, for that exact reason; my very first AoS purchase was Start Collecting! Malignants, containing nearly the whole of the pre-2.0 Nighthaunt line within. To expand upon their importance, we only saw the sunsetting of Start Collecting! as a line with the final box to be removed, Flesh-Eater Courts, taken off of shelves in 2023. Even then, current players bemoaned its removal, as a means to obtain essentially every core unit in a single discounted box. Many players began their journey into Warhammer with this series of releases, and it’s vital to recognize that not just their contents, but their price point, were to blame. AoS needed to sell itself, because its player base was shockingly new, and not broadly a group of Warhammer Fantasy Battles players who had remained after the game’s transition.

January 21st, 2016 came with a refresh to Age of Sigmar’s page on the Games Workshop website, alongside the release of its next new faction, the flame-bearded Duardin, the Fyreslayers. This UI update came with the division of the game’s factions into their respective Grand Alliances (a theme we’d see expounded upon shortly after) and 23 factions available (with most still being holdovers from Fantasy). This was the first introduction to many of the new names being used for armies & units, which received mixed reviews, in the same vein as the launch of the game itself. Many players speculated that these names were due in large part to a refresh of copyrights attached to the IP (which isn’t wrong), but it also gave AoS more room to distance itself from its predecessor. These new names helped to give the game a more high-fantasy flair, and as more time has passed, these titles are all the more well-regarded.

![]()

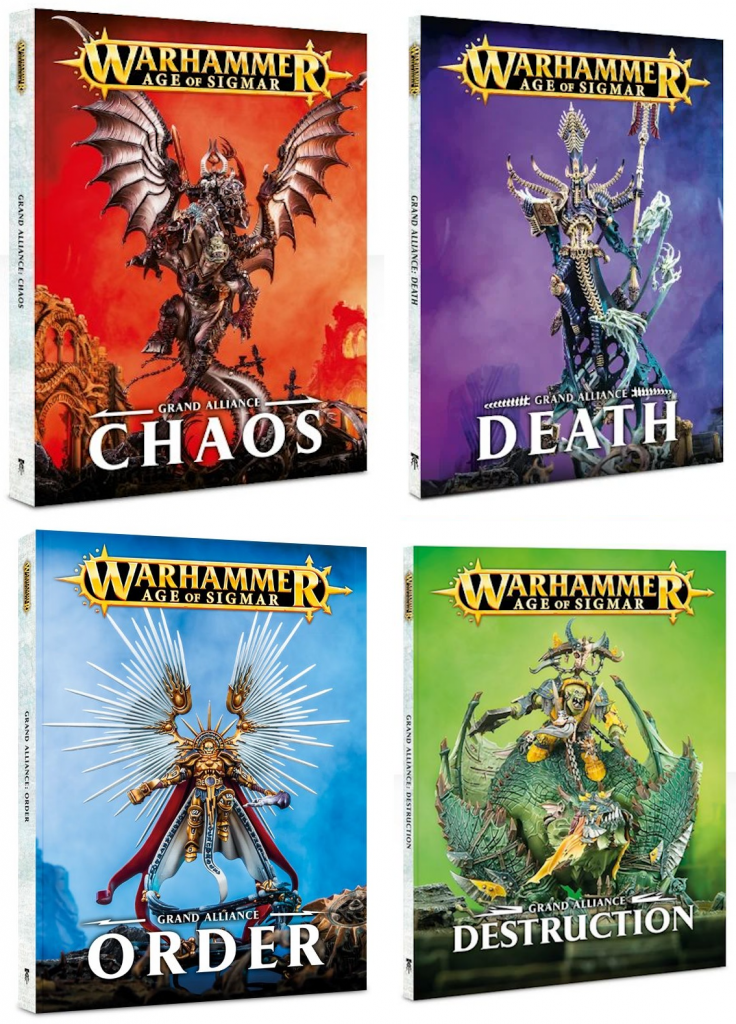

Fyreslayers were one of the first major breakthroughs in something AoS has strived to innovate upon: The power of context. This is an idea that started small, out of necessity, but has become the lifeblood of the game itself. While the Fyreslayer release in January & February of 2016 only had a dozen or so models, each kit had multiple builds, weapon options, or spare heroes, giving the faction some ‘meat’. You could purchase a Magmadroth, and receive 2 extra heroes on foot, each of which had a role unto itself; this was true of a few key pre-End Times Fantasy kits as well, but has since dwindled for all but the most complex releases. That said, recontextualizing these few kits would be a strategy employed by AoS for many of its most famous armies, namely Flesh-Eater Courts, but it first saw widespread use in this initial wave of Fyreslayers. Even today, there’s a host of factions which never saw a full-scale second wave beyond their debut (We’ll talk about the Kharadron & Idoneth next time), so allowing their subfactions to help specialize how each plays the scant units in their product line really is a fantastic facet of Age of Sigmar. February 2016 also saw the release of the first of four mega-books, Grand Alliance: Chaos.

Grand Alliances, Fractured Factions

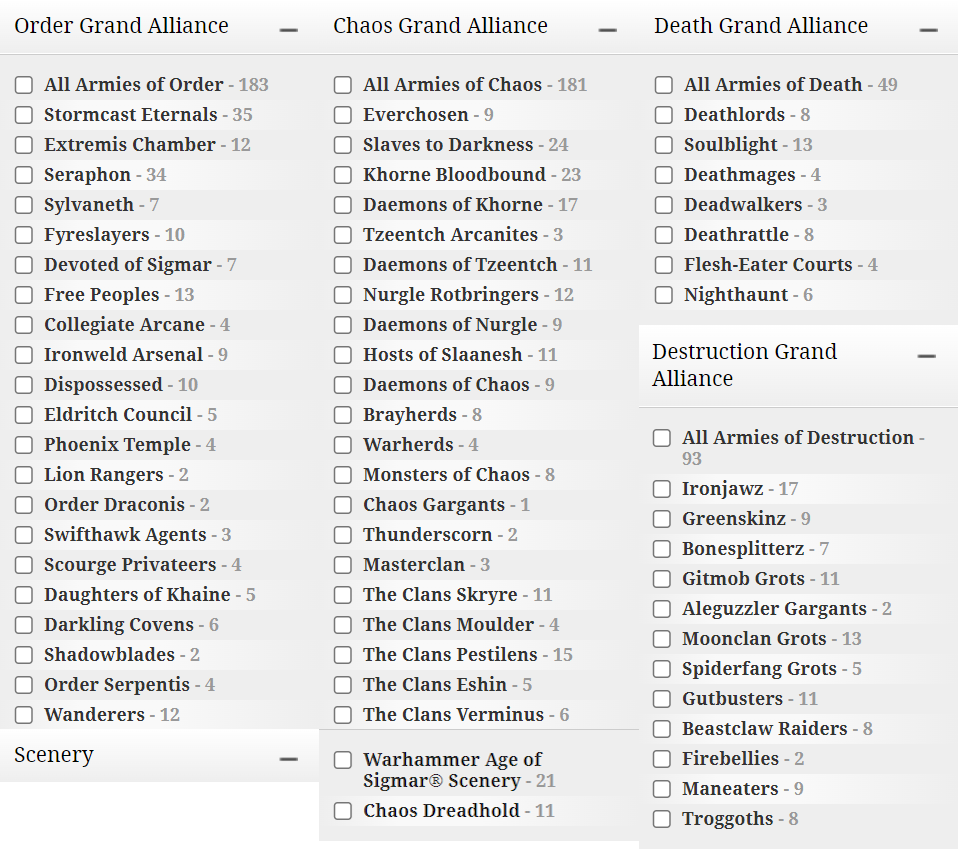

Beginning in Grand Alliance: Chaos, there was a splintering of the existing factions into more trademark-friendly nomenclature, although it quickly gave Age of Sigmar the record for the greatest number of legal factions of any Warhammer property, once each of these books came out. Following GA: Chaos, factions like the Beastmen took on different names, from Brayherd, to Warherd, to Thunderscorn, with each crucially being advertised and treated like their own army. This meant Chaos went from 9 factions to 21 while gaining not a single model.

In some ways, this allowed hyper-thematic army construction to emerge, and for a few select armies, this idea of spinning off every subset of a faction led to fantastically flavorful forces which persist today, the poster child of which is Flesh-Eater Courts. As another note, this was the end of the ‘comedic’ rules associated with the launch period of Age of Sigmar, as every GA made sure to prune these rules and give the game a more serious tone, as an effort to be rule-forward. This contrasted the prior sentiment of Games Workshops’ board, and represented a change of leadership for the brand as a whole.

That’s right: It took only ~4 short months for Games Workshop to completely wash their hands of the maligned roleplay rules that the launch had become infamous for, which goes to show that the push towards digitalization and rapid releases allowed the AoS team to play a more ‘reactive’ game with the market in mind. Grand Alliance books continued to release month by month, with few model releases trickled out for the two starter factions (SCE & Khorne), in the order of Chaos, Death, Order, and finally in May of 2016, Destruction.

Chivalry, and Mummies, Are Dead

March & April were notable for two things: The announcement that Bretonnia & Tomb Kings would be sunsetted (or ‘squatted’) in March, and the release of the Ironjawz range in April, just before their Grand Alliance: Destruction tome. While Bretonnia received a statement of closure, being cited as part of Games Workshops’ effort to keep their model lines fresh, the only indication of Tomb Kings’ removal was their absence from Grand Alliance: Death. While each army had Legends rules updated through the start of 2.0, part of the shock that came from this decision was the fact that Tomb Kings had gotten a relatively-new plastic release in 2011, with models in their line far newer than that of Bretonnia, or especially Skaven.

While the player bases for these armies was meager, part of the reason they were chosen to cease production, it only further cemented these vocal minority’s’ grudge towards the game which saw their armies removed. Ultimately, hindsight might reveal that it would have been smarter to keep or update these factions, as Ossiarch Bonereapers (and to some extent Cities of Sigmar/Flesh-Eater Courts) essentially replaced them later on. Speaking from a modern perspective, there was clear care in rebooting these two removed factions for The Old World, and while the resources available for doing something like that simply didn’t exist at Games Workshop in 2015, plenty of armies have held firm to their Fantasy kits for just as long.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Silver Tower

May of 2016 was an incredibly eventful month for AoS, as it contained the relaunch of Warhammer Quest, in the Silver Tower adventure (which also served to provide Tzeentch a setting-specific range). This RPG was a departure from the traditional wargames that Games Workshop had become famous for, harkening back to its roots in TTRPG publication, and the birth of Fantasy. Many of its models were immediately ported into the larger system, and it served to bolster the ranges of a diverse array of armies. Some remain in production today, such as the Ogroid Thaumaturge & Kairic Acolytes, but strangely, many have gone without rerelease even when they would fit right in. On the whole, the only models to be removed from AoS that were first sold during its time as a system tend to come from early box sets like this, or undersold Underworlds products — In the grand scheme of things, sculpts have aged remarkably well, meaning even early releases comfortably stand alongside current models.

This set a precedent for Age of Sigmar that has remained to this day, that secondary releases for the setting have cross-system play in some capacity. Later on, we’d see this in the form of Warhammer Underworlds & Warcry, but Silver Tower was a watershed moment to make sure any Age of Sigmar model could be played in Age of Sigmar. That’s not all, however, as May also came with the Battletome for Flesh Eater Courts, a stand-out bit of lore for the game which bore a tongue-in-cheek nod to the removal of Bretonnia, beginning the joke that chivalry remained alive, in the form of these former Strigoi. Additionally, this period marked a trend towards saturation of color within model paintjobs; it’s no secret that early AoS tried its best to be bright on the packaging, and between the bright yellow & green of Ironjawz, to the blinding full-body gold of the stormcast, the more lifelike tones of Fantasy began to be phased out for new releases. This is a contentious topic to be sure, but did a lot to make new-to-AoS models stand out on store shelves, and the updated webpage.

When Are We Getting Start Competing: Lion Rangers?

Following the May releases, each of the Grand Alliance books had bolstered their respective forces with a number of factions, each of which was generally 6 or fewer kits (if you were lucky). The Empire saw itself spun off into the Collegiate Arcane, Ironweld Arsenal, Free Peoples, and Devoted of Sigmar, as an example; all of this splintering came to a head just before the first General’s Handbook, and as foreshadowed, Age of Sigmar reached 62 playable factions, offset by a near-total lack of army construction or faction-specific rules. Instead, Warscrolls were internally-complete for the majority of factions that had not received a Battletome at this time. This was still an era where there were no abilities shared between factions, something foreign to how armies now function. Instead, each ‘micro-faction’ generally had one or more Warscroll Battalions, collections of units you could take and give each a shared rule, the only means of tying together broader swaths of models (these worked much like the Formations of 40k 7th edition). This would later be further refined into shared Grand Alliance rules in General’s Handbook 2016, and then true faction abilities in the 2017 iteration, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Just to muse on the absurdity of this point in Age of Sigmar’s history, imagine an alternate history where something like Swifthawk Agents, Sigmar’s aelven postal service made up of Island of Blood High Elves and Skywardens, got the full-faction glow up of something like Daughters of Khaine. It was impossible to predict which factions might be recombined, removed, or given a facelift, and that chaotic era is something I imagine won’t ever be replicable. We take for granted how static the armies of current AoS (and 40k) tend to be: This point was the only time in any Games Workshop title’s history where the fates of ones’ army was so thoroughly unpredictable. As someone who started Nighthaunt around this time, I can attest to that much.

![]()

As I said however, a few factions did receive their own faction books during this period, such as Stormcast Eternal, Everchosen (Archaeon, the Gaunt Summoner, & Varanguard), Skaven Pestilens, and Seraphon. It would be impossible to cover each in detail, but their impact lay in the groundwork each set up for their respective army: Seraphon became dream-formed daemons of Order, and the Eightpoints was constructed as a proving ground for Archaeon’s faithful. That said, these lacked true subfactions, which would begin being rolled out only once the overall faction number began being pruned, in late 1.0 through 2.0.

To wrap up this chapter in Age of Sigmar 1.0’s history, it began its life with what can only be described as the inverse of goodwill: It was forged as an attempt at a fiscal miracle for Games Workshop, burnt every bridge it could with Fantasy’s deeply entrenched playerbase, and took nearly a year to take itself seriously as an intricate wargame. Still, there were lessons learned early on, which wouldn’t have been possible within the context of Games Workshop’s prior business model: Rules were rolled out rapidly, and changed frequently, as a stark contrast to the static army book releases of years prior. New models were dynamic, and contextualized within a higher-fantasy world not just by being more hyperthematic, but painted in saturated colors that are now iconic to the aesthetic of early AoS.

Set against literally all odds imaginable, it was the scrappy newcomer to an established brand that had much to prove, and maybe even some tournaments to its name in the near future. It’s the opinion of this author that, had the release been handled more smoothly, and the company had been provided more time to transition, much of the ongoing grumbling surrounding AoS could have been avoided. There will always be those who wished Fantasy never went away, but as I hope can be seen through this brief history, frankly its disappearance was for the best. Games Workshop had no opportunity to retain a fantasy IP if not via a reboot, and for all its changes and initial faults, Age of Sigmar showed promise from very early on. Following these first real steps towards a wargame recognizable to a current player, the release of General’s Handbook 2016 was about to change everything, and introduce an era not only of points and an emergent tournament scene, but some of the lore & factions this game is thereafter beloved for.

Next Time: The General’s Handbook Era: July 21st, 2016 – August 8th, 2017

That wraps up our initial look at the launch but in our next article we’ll look at the first General’s Handbook for the nascent game. In the meantime, if you have any questions or feedback, drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.